I cannot think of a better time to be twenty-six years old. There was, for example, that night a year ago in Budapest. Sixty of us swayed in a circle, our arms locked around one another’s waists, singing. Above us was a full moon; the lights of the city glowed a soft blue and orange below us. It was two in the morning; most of us were exhausted, but no one had any desire to leave. We had gathered from every corner of the planet-from east and west, north and south, from more than twenty countries and every kind of political system and cultural heritage. We spoke more than a dozen languages. But on this night, communication posed no problem. As the melodies and languages rang out across the silent, silvery-dewed meadow it became clear that we were celebrating our diversity and our unity at the same time. For one night, on top of a mysterious hill in central Europe, we had created the united world of our dreams.

The members of the circle were physicians and medical students who had attended a conference sponsored by the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, an organization that a few months later would win the Nobel Peace Prize. Whenever I try to define my images of a peaceful world, I invariably think of that spontaneous, latenight celebration in the meadow. Each person represented a culture and a particular region of the earth, yet each person was also recognized and respected as an individual human being. At the same time we were also a collective organism, moving in harmony and linked by our common dreams, hopes, and laughter

Only a few generations before such a gathering of young people from all over the planet would have been a technical and political impossibility. Yet it was also only a few generations ago that humans acquired the ability to destroy the earth. Ours is a time of accelerating extremes. Never before has the danger been so great-never before have the tools available to us to meet that danger been so powerful. With the technology of space-based missile systems has come the technology for global satellite communication. As the darkness grows so does the light; as the tools of darkness advance, the tools of light advance in step.

In every crisis is an opportunity. What had brought us to that Hungarian meadow and allowed us to overcome barriers of distance, money, language, and indifference was the urgency of the common danger we knew we faced. Perhaps only a threat as huge and allencompassing as the threat of nuclear war could do what it is doing today: forcing people all over the world to communicate, to pay attention, to stretch themselves, to really try to understand what is going on, to try to come to terms with our differences and figure out ways to live with each other, if not in utopian peace, at least a long way from the brink of holocaust.

The opportunity inherent in the nuclear crisis is that we are being forced, as a species, to grow up in a hurry. I sometimes think that nuclear arms are part of a kind of grand coming-of-age ritual-a test to see if we can move past adolescence into maturity. It’s a terrifying test; and we may not pass. But it also makes this an exciting, vibrant time to be alive. I can’t think of a better time to be twenty-six years old.

Looking at the world with a “realistic” eye, there are few objective reasons for hope. Our president, after great pondering and hoopla, decided in 1985 to advance our country to the brinkof 1958, by holding a single summit meeting with the leader of the Soviet Union and signing a cultural agreement that is already in deep trouble because of his administration’s refusal to provide any government funding for such exchanges. Star Wars, which may eventually win a historian’s prize for the worst idea of the twentieth century, is proceeding apace with the Soviet Union now plunging into its own version of Star Wars research as part of the eternal game of “keeping up.” The Reagan administration’s idea of a policy debate on arms control treaties appears to be whether to scrap American adherence to one, two, or all of the above. The Euromissiles are being deployed, the Geneva negotiations are boringly and predictably stalemated, and both superpowers are going broke trying to pay for it all.

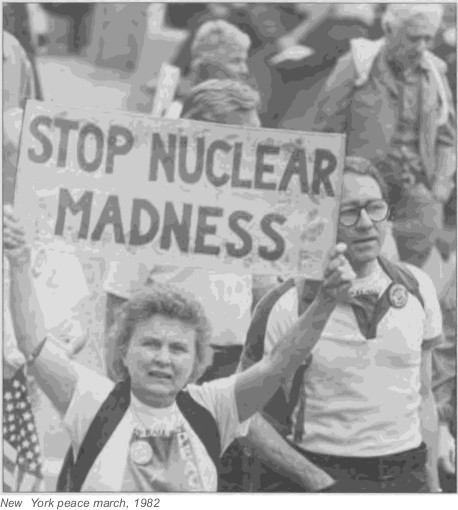

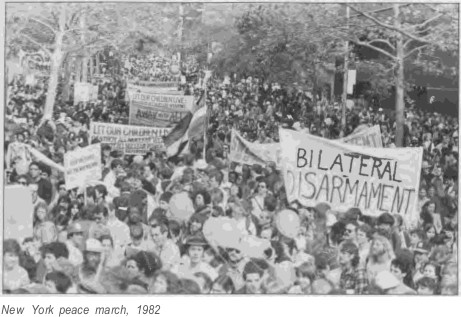

Yet, at the same time, unprecedented numbers of people around the world are beginning to act. In the past two years I have had the opportunity to interview dozens of these people while writing a book called Citizen Diplomats. Each of them is trying in some innovative way to make an end run around the current stalemate in government-togovernment diplomacy. Each of them has made direct contact with people in the Soviet Union and the other countries commonly considered The Enemy. Each believes that getting rid of the bombs is only half of the task before us; the other half is transforming relationships between nations so that war becomes impossible. Each believes that such a transformation will require the active participation of ordinary people on both sides of the Cold War.

The crucial step is convincing ourselves that individuals can make a difference. Right now many persons’ only relationship to foreign policy is listening to Dan Rather talk about it on the evening news. They feel no more capable of affecting it than they feel capable of walking into their television sets and beginning to converse with Dan in their living rooms. But strange things happen once people start doing things. Dr. Bernard Lown, one of the founders of the physicians’ peace movement, says simply: “Activity breeds optimism.”

Declaring earnestly that nuclear weapons ought to be junked is clearly not enough. The American public finds itself caught in a dilemma. Few really like nuclear weapons; almost everyone is afraid of them, but many Americans are also deeply afraid of The Enemy, commonly represented in our time by the Soviet Union. Until the fear of The Enemy is reduced to a more manageable level, rational arguments for arms control, for a nuclear freeze, a comprehensive test ban, and many other sensible proposals are not likely to go far. People have a hard time hearing about the virtues of these arguments while “What about the Russians?” is thundering in their ears.

Meeting some of the people at whom our bombs are pointed is one way to gain perspective on our fears of The Enemy. On my first visit to Hungary I wandered around the streets of Budapest in a daze, unearthing and discarding the images I only then realized had been embedded in my expectations: policemen on every corner ready to snatch my notebook away; crowds of faceless, unsmiling people dressed in gray uniforms; dulled and robot-like children; unmarked, dirty gray buildings. 1 remember playing with hair-ribboned little girls in public parks and thinking, over and over: “My government has at this very moment nuclear weapons aimed precisely at you.” It doesn’t take long before a rather simple conviction takes root: no political or ideological differences in the world can justify the risk that we might blow up the planet.

One goal of citizen diplomacy, then, is to accelerate and comp1ement the efforts of those working to persuade leaders to stop building weapons. A second goal is to ensure that, in the meantime, the weapons “rust in peace.” If our NORAD early warning systems suddenly told us that Great Britain had launched a nuclear attack on the United States, we’d say phooey, another flock of geese. We wouldn’t believe it for a moment. Even though Britain’s weapons are sufficient to trigger a nuclear winter and could fairly effectively wipe the United States off the map, we don’t live in fear of them. Britain is an ally; our countries are linked historically, culturally, politically; even more importantly, the citizens of our two countries are closely linked through family, business, and other personal ties. If Thatcher and Reagan tried to declare war on one another, they’d be hooted out of office.

What we need to do is create a similar kind of web of citizen relationships between the peoples of the United States and the Soviet Union. We are well on our way toward creating such a web of relationships with China, which not so long ago was the feared “yellow menace” at which our nuclear buildup was primarily aimed. Now, as Arthur W. Hummel, Jr., one of President Reagan’s former ambassadors to China recently said: “We no longer need to plan for the possibility of a war with China. The multiplicity of relationships which we have-perhaps the majority of them having nothing to do with the U.S. government-is a genuine stabilizing force.”

My favorite metaphor for citizen diplomats is one of Lilliputians tying down the giant Gulliver with thousands of tiny strands. The giant is our knowledge of how to make atomic bombs, a genie we cannot fit back into the magic lamp. But the total effect of millions of individual relationships between people in different countries all over the world can weave a sturdy fabric of international stability that can prevent that giant from stirring. What eventual form that fabric will take has yet to be imagined. No matter. The process of spinning those threads is already underway, and everyone can be a weaver.

One potential pitfall is to see such a solution as complex and therefore hopeless. It is complex, no doubt about it. Then again, so is the European railway system. So is walking. Complexity alone is no reason for despair. We don’t always have to know exactly what we are doing as we are doing it. We only have to have a feeling for why

Another pitfall is to believe that unless we can detect a definite change in the world as a result of what we are doing, we are failing. But the nature of change is subtle. What may seem at the time to be sweeping changes may be thoroughly temporary; what may seem to be so much headbeating against a wall may in fact be creating change in ways no one will ever be able to exactly trace. As Gandhi put it so beautifully, what each of us does may seem insignificant at the time, but it is terribly important that we do it. It could be that all the ingredients for a peaceful transition to a peaceful world are already around us, already simmering away nicely, and it is only our limited vision that prevents us from seeing this.

Personally, I don’t trust peace scenarios that are neat and tidy. The world is too complicated, too influenced by the bizarrely coincidental for such blueprints. Too rigid an idea of where we’re going can keep us from getting there. As one citizen diplomat recently told me, “Goals can sometimes get in the way of progress.” There are no magic recipes out there, no fixed solution we are heading toward-there is only something waiting to happen, a process to start participating in, principles to start living by.

Most images of a peaceful world seem to emphasize a tremendous distance between a blessed, far-off peaceful existence in the future and the world we now live in. Accompanying these images is the idea that we have a very long “road” or “path” to traverse before we arrive at this remote, wonderful, fairyland destination where everything is magically different and changed.

My own images differ. I believe that a peaceful world is not a destination in a distant future where we might eventually a r r i v e – I believe that it is all around us, at this very moment, and that every one of us, every day in our lives, catches some glimpse of it. There are dramatic glimpses, such as the gathering in the moonlit Hungarian meadow. But my life is also strewn with smaller, quieter glimpses of that vision: a letter from an East German friend, a well-crafted piece of pottery, a happy baby, an integrated classroom, a foreign language course, a wilderness area, an African dance festival, a class in birdwatching. Much of that world is already here, already now, if we choose to look at it that way.

When asked how he had sculpted his famous statue of Moses, Michelangelo replied that Moses was trapped inside the marble, and all he had to do was to chisel away everything that didn’t look like Moses. I think this is a beautiful image for the task before us. The world we would like to create is inherent in the rough-cut hunk of marble that is our world of today. It is up to each of us to learn how to heft a hammer and a chisel and chip away everything that is not part of a peaceful world.