Gale Warner and David Kreger

American voters will soon decide whether to re-elect President Ronald Reagan for a second term in office. President Reagan’s major statements, proposals, policies and actions on a wide spectrum of issues are the subject of heated debate. The following is a summary, drawn from publicly available sources, of the Reagan Administration and how it has affected Americans and the world.

The Economy

In the past 15 years, the U.S. economy has taken a roller-coaster course through a series of recessions and recoveries. Though presidents’ policies have had an important influence on the economy, they have by no means dictated it. The president writes the federal budget and sets levels of government spending and taxation. The Federal Reserve Board, which is not under the president’s immediate direction, controls the amount of money in circulation and thus can directly influence the interest rate and inflation.

The cycle of inflation, recession, and recovery tends to run by itself. The era of high inflation began largely with the sudden oil price hikes in the early 1970s, which sent shock waves through the economy. This created higher prices, causing workers with built-in cost-of-living wage increases to receive salary hikes. Since labor costs significantly affect production costs, the price of goods increased and sustained inflation was underway.

The Federal Reserve, in order to reduce inflation, can decrease the amount of money in circulation. This makes each dollar “more valuable”, and helps keep prices down. But with less money available, there is more competition between potential borrowers, so Interest rates for loans Increase, reflecting the increased competition. Whenever loans are more expensive to obtain, business slows, workers are laid off, and there is less investment. In a depressed economy, people purchase fewer things—demand decreases—and therefore prices come down. That is, a recession causes a reduction in inflation. The Federal Reserve cuts Inflation, but only by increasing the number of jobless.

Lower inflation allows interest rates to come down since it is the difference between interest rates and inflation—the “real interest rate”—that reflects the true cost of borrowing money. As interest rates lower, production, consumer spending, and Income—indicators of economic growth—begin to rise. This is called a “cyclical recovery.” With the recovery comes more job opportunities, though after each recession unemployment has remained higher than before the recession.

The forces causing the recession from which we are now recovering had been building for several years. Inflation was spiraling upward, and it was widely agreed that something had to be done. President Carter faced a choice between two evils—high inflation or high interest rates. To show he was a serious inflation fighter, Carter appointed Paul Volcker to head the Federal Reserve Board. Volcker, a highly respected economist, has earned a solid reputation for acting Independently, and Carter got even higher interest rates than he bargained for. Volcker changed the Reserve’s policy in October 1979, tightening the money supply, and soon the Interest rate soared above 21 percent, causing a recession that lasted from late 1980 through 1983.* As inflation fell from its peak of 11.3 percent in late 1980 to 3.8 percent in late 1982, unemployment rose from 7.5 percent to 10.7 percent, breaking the post-war record. Some criticize Volcker for being too drastic and causing more unemployment than necessary.

The 1980 election occurred just after the Federal Reserve tightened the money supply. The 1984 election will occur in the middle of the cyclical recovery. Because of this sort of timing, Carter was one of the unluckiest presidents seeking re-election—and Reagan is one of the luckiest.

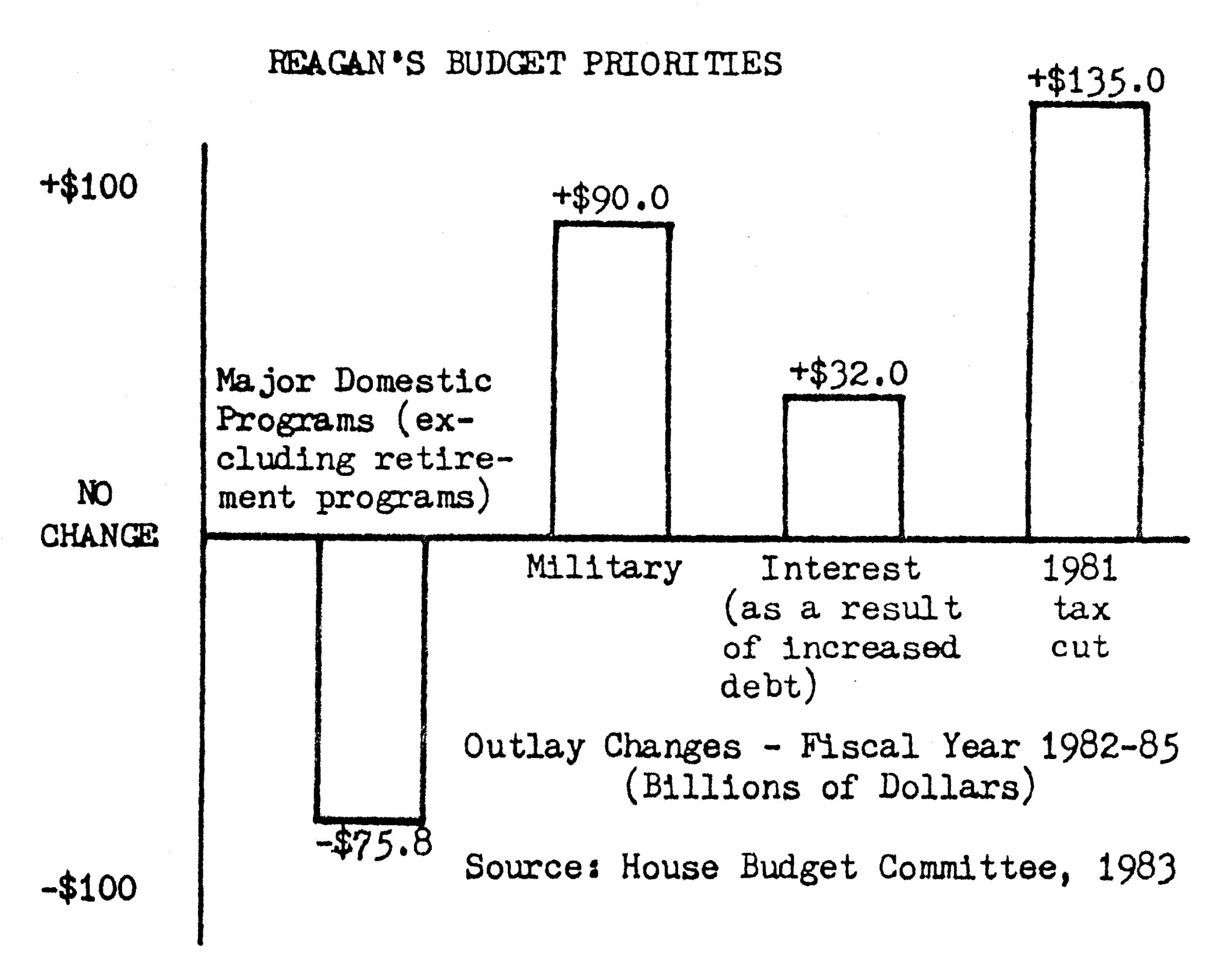

The Reagan Budget

Reagan’s dramatic cuts in social programs have not been enough to offset his even more dramatic increases in spending and the loss in federal revenues due to the 1981 tax cut. This imbalance between the inflow and outflow of money from the Treasury has created a record-breaking annual deficit that is causing fundamental economic problems.

Taxes

The 1981 tax cut, the largest in U.S. history, abolished a fourth of personal income tax and slashed corporate taxation deeply. It was estimated the U.S. Treasury would lose $750 billion over the next five years. Most of the money was returned to those in upper-income tax brackets. According to the Treasury, 4.4 percent of all taxpayers—those with Incomes of $50,000 a year or more—are receiving one-third of the benefits from the tax cut. The non-partisan Congressional Budget Office analyzed the cumulative effect of budget changes between January 1981 and April 1984 and found that low-income families had lost the most and high-income families had gained the most. Households with incomes less than $10,000 a year lost $390 a year, on average. hose with incomes between $40,000 and $80,000 gained $2,900 a year, on average; those with incomes of $80,000 or over gained an average of $8,270 per year. Middle-income families gained only slightly: households with incomes from $10,000 to $20,000 per year gained an average of $30; those between $20,000 and $40,000 gained $1,010 per year.

These results are not surprising considering Reagan’s long-held belief that taxing the rich at a higher rate than the poor is unconstitutional and comes “direct from Karl Marx.” Reagan also believes “there really isn’t a justification” for the corporate tax, saying “only people pay taxes.”

Supporters of the tax cut argued that the money returned to the wealthy and to corporations would spawn investment in new business ventures that would create new jobs and “trickle down” to those hardest hit by the recession. However, there is a great deal of evidence that increased investment following the tax cut did not occur; instead, consumption rose. The wealthy simply bought more, and the money never reached those who needed it most.

Spending

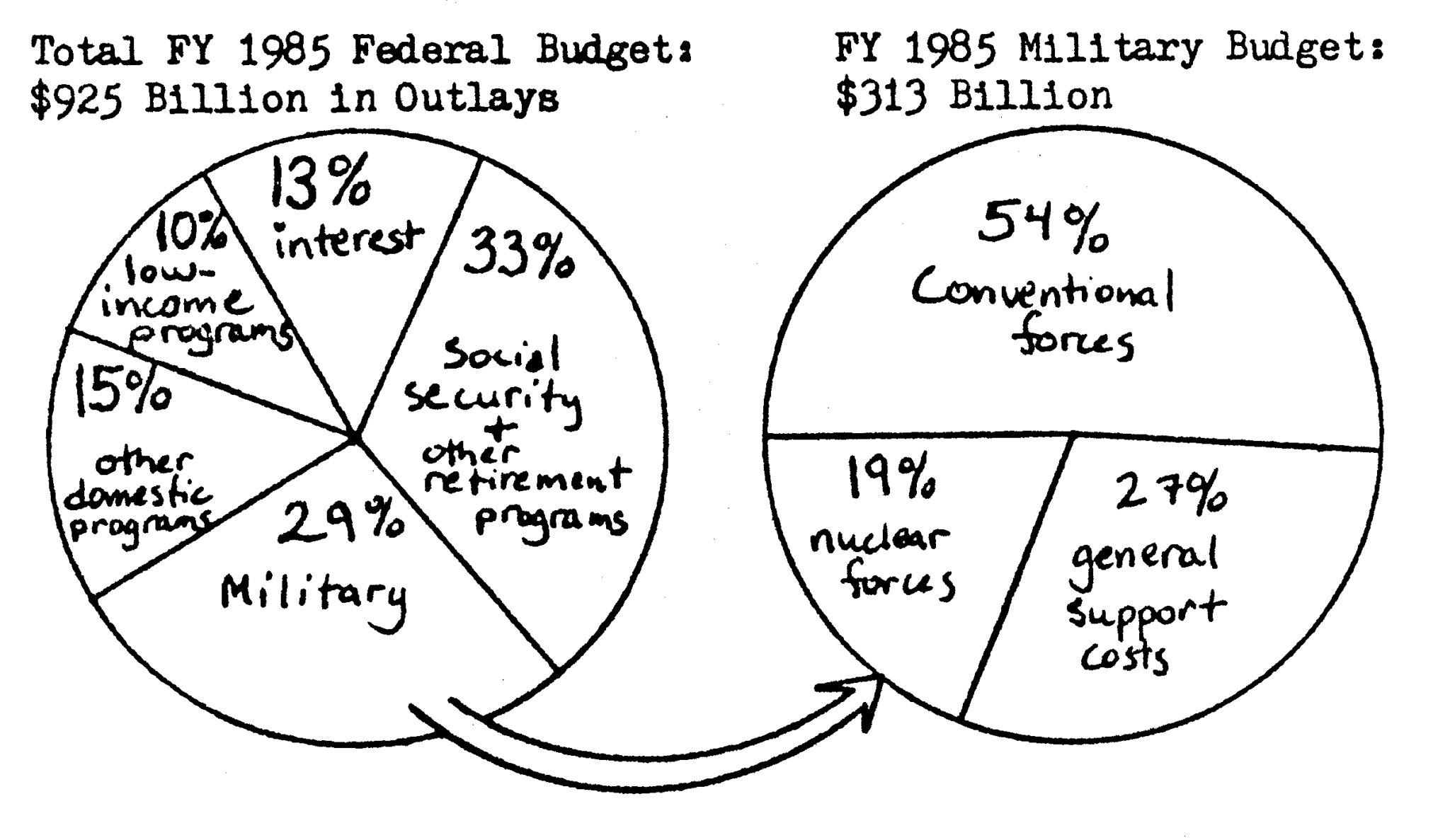

Reagan is responsible for the largest peacetime military build-up in U.S. history. While Carter’s fiscal year 1981 budget called for $182.4 billion, Reagan’s fiscal 1985 budget calls for $313.4 billion, with further increases each year to $436 billion in fiscal 1989. From I985 to 1989, he plans to spend $2 trillion on the military. This compares to a total of $1.8 trillion spent between 1960 and 1981.

Human services—food aid, health programs, job training, veterans’ benefits, housing aid, Social Security, education, and so on—have been cut $110 billion between fiscal 1982 to fiscal 1985. Had all Reagan cuts been adopted as proposed, the figure would be closer to $140 to $150 billion. These cuts have inflicted heavy costs on millions of working and needy Americans; the “savings” have been transferred to the military.

In spite of these cuts, Reagan has continued to increase overall federal spending. In fact, according to Republican figures adjusted for inflation, he has not even decreased the rate of increase in spending. Carter’s fiscal 1981 budget was a 14% increase over 1980, but inflation was 11.3% In the last quarter of 1980 when the budget was finalized. Thus, the growth in real dollars was 2.7%. Reagan’s fiscal 1984 budget was a 7.2% increase over 1983. But inflation was 3.9 percent in the last quarter of 1983 when it was finalized. The growth in real dollars was 3.3%, larger than Carter’s 2.7%.

The Deficit

The federal deficit was $57.9 billion in Carter’s last year. In fiscal 1993, it was $194 billion, and it is predicted to be $280 billion in fiscal 1989. Our national debt at the end of fiscal 1985 will stand at $1,852 billion, $853 billion of it a legacy of the Reagan Administration.

The massive cuts in social programs have not made up for the military Increases and the loss of tax revenues. Even if all non-military discretionary spending were eliminated, the fiscal 1988 deficit still would be $70 billion. There simply are not enough social programs in existence to make room for Reagan’s military increases and tax cuts.

Yet while lobbying for the tax cuts, Reagan promised a balanced budget in fiscal year 1984. He told Americans: “Now there are those who are Insisting that we settle for less (than the 25% tax cut). They demand proof in advance that what we propose will work…Our opponents want more money from your family budget so they can spend it on the federal budget and make it remain high. It’s your money, not theirs. You earned it, they didn’t…And when they insist we can’t reduce taxes and spending and balance the budget too, one six-word answer will do* ‘Yes we can and yes we will.'”

When the budget deficits became a reality, the president said on November 16, 1982: “A propaganda campaign would have you believe these deficits are caused by our so-called massive tax cut and defense buildup. Well, that’s a real dipsy doodle. …Current and projected deficits result from sharp increases in non-defense spending.”

As part of a recent “down payment” plan to reduce the deficit over the next three years taxes have been raised $50 billion and social programs cut by $13 billion. No defense cuts have yet been approved. Even this plan is only making a small dent in a huge problem. Over the next three years, deficits are projected to total $600 billion. Reagan wants to cut $77 billion more—largely, he says, by vetoing expenditures on social programs.

Impact of the Deficit

Real Interest Rates Remain High. The amount of money banks can lend out is limited by the amount deposited in their savings accounts. When the government “deficit spends,” it borrows from banks (and pays interest on the loans). The nearly $200 billion deficit is more than three-fourths of all the money saved by Americans each year, compared to the 1980 deficit, which was about one-third. This leaves little for private borrowing. Since interest rates reflect the increased competition for the remaining money, this is a main reason the real interest rate (interest rate minus inflation) is now above 9%, still very high.

The interest rate would probably be higher if foreign capital were not pouring into U.S. banks, increasing the amount available for lending in the United States. The capital is coming in because the United States is further along in its recovery than most other countries. When they catch up, the influx will slow down.

Reagan has created a confidence problem. Because people in the financial world expect the interest rate to rise because of the deficit, demand for loans right now is increasing, boosting the interest rate still further (13% in July 1984). Many predict the massive Reagan deficit will ultimately lead to the same dilemma Volcker faced in 1979.

Trade Imbalance Soars to All-Time High. High-interest rates induce foreign investors to buy dollars and deposit them in U.S. banks to earn high interest. This increased demand for dollars increases the value of the dollar on the foreign exchange, meaning that U.S. products become expensive for foreign consumers, while foreign goods become cheap for U.S. consumers. The results are increased imports and decreased exports. In fiscal 1981, the balance of trade was negative $28 billion. In 1983, it reached negative $70 billion, an all-time high. In 1984, it is expected to top a negative $100 billion.

One out of five jobs depend on the export trade; since 1980 the exchange rate imbalance has cost 1.5 million jobs. Multinational corporations tend to invest outside the country where labor and materials can be purchased easily with bloated dollars, and U.S. firms suffer permanent damage as foreign firms push them out of markets.

Small Business Suffers. With large federal deficits, small business is crowded out of the credit market by the high-interest rates and intensified competition with big business for a share of the diminished funds available for borrowing. In this credit struggle with big corporations, small business usually loses. Small businesses are often charged rates above the prime rate because banks deem them less creditworthy and a greater risk than their big business customers.

World Economy Suffers. High-interest rates in the U.S. encourage companies and individuals to draw capital out of other countries for deposit in the U.S., thus inhibiting other countries from recovering from the worldwide recession. To stop this capital drain, other countries are forced to raise their interest rates, fueling further recession.

High interest rates also increase the danger of default on the United States’ $150 billion loans to the third world, threatening the stability of the world financial system.

WHAT IS REAGAN GIVEN CREDIT FOR?

Curbing Inflation. Inflation, which reached a peak of 11.3% at the end of 1980, is expected to average 3.9 percent from November 1983 to November 1984.

The drop in inflation is largely due to the recession itself. The recession meant economic hardship, and therefore, less demand and lower prices. Also, falling oil prices resulting from the temporary world oil glut, as well as bumper crops leading to lower food prices, have brought down inflation.

Decreasing Interest Rate. In January 1981—when Reagan entered office—the prime lending rate was 21.5%. In mid-1984, it was 10.5%.

In 1980, the Federal Reserve caused the interest rate to soar from 11% to 21.5% in an effort to curb inflation, spawning the worst recession since World War II. The decline in the interest rate to the pre-recession level represents a cyclical recovery from the recession. The rate is climbing, however, to 13 percent in July 1984, and is projected to reach 14% by late 1984.

An important measure of the cost of borrowing money is the “real interest rate”—the difference between the interest rate and inflation. For example, if the interest rate and Inflation are equal, then in effect it costs nothing to borrow money: the extra value you get from having the lump sum early is equal to the Interest you have to pay, so the real interest rate is zero. Because inflation has fallen along with the Interest rate, the real interest rate has remained nearly constant. At its highest, it was 11%, and it remains a hefty 9.1% hampering business investments in plant and equipment that are critical for a lasting recovery. The Reagan-caused deficit threatens to keep the real Interest rate high.

Economic Growth. According to the Republican National Committee, the economy grew 6% during 1983, and unemployment has fallen from 10.7% in November and December 1982, to 7.5%t in May 1984.

In recovery from the worst recession in over 40 years, economic growth is no surprise. Unemployment remains higher than pre-recession levels under Carter, which averaged about 6.6%. The economic recovery has occurred not because of Reagan’s policies, but in spite of them. Reagan’s deficit may thwart any long-term recovery.

Bias in Favor of Big Business

Big Vs. Small Business. Comprising 97% of all U.S. corporations, small business employs one half of the American workforce, creates virtually all new private sector employment, and provides greater opportunities for laid-off workers, women, minorities, and first-time job seekers. Small businesses, however, have been failing at record levels. In 1983, 30,794 small businesses failed, a number comparable only to the 31,822 failures of 1931.

Despite this crisis, Reagan’s corporate tax cuts favored big, not small, business: 80% of the money went to big business, with only 20% going to small business.

Gutting Antitrust. For assistant attorney general in charge of the Justice Department’s antitrust division, Reagan appointed William Baxter, a self-described “harsh critic” of antitrust laws. “The antitrust laws,” he said, “interfere with a lot of efficient business practices.” Baxter told the judge who was presiding over the ten-year-long IBM trial to dismiss the case because it was without merit. The judge then publicized that Baxter had been a paid employee of IBM on several occasions. Baxter has moved to strip the Federal Trade Commission of “all its antitrust jurisdiction.” The three largest mergers in U.S. history, all involving oil companies, occurred in the first two years of the Reagan Administration. During Reagan’s term, three of the government’s four major pending antitrust suits have been dropped and the fourth one settled under controversial terms.

The National Labor Relations Board. The NLRB was established in the New Deal era to guarantee workers the right to choose whether they wish to be represented by a union, and, if so, which union. It was meant to guarantee that collective bargaining is conducted in a civil, orderly manner. The members of the NLRB have traditionally been reasonably impartial figures. For chairman of the NLRB, however, Reagan appointed Donald L. Dotson, who believes “collective bargaining frequently means labor monopoly, the destruction of individual freedom, and the destruction of the marketplace…unionized labor relations, shortsighted demands, greed, and debilitating work rules have been the major contributions to the decline of once healthy Industries. …The way has been paved by the NLRB.”

Dotson transferred considerable enforcement authority from an independent general counsel to Hugh Reilly, who had spent the previous eight years at the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation, a right-wing organization that supports employers, never workers, in management-labor disputes.

Dotson and Reilly have partly dismantled the NLRB. Since 1980, the backlog of undecided unfair labor practice cases has grown to unprecedented levels. From September 1983 to February 1984, the total number of decisions in unfair labor practice cases was 259, compared to 625 and 638 in equivalent periods of time under Ford and Carter. In the cases that were decided, disproportionately few were ruled against employers, while disproportionately many were ruled against unions. The NLRB ruled against employers in only 68 cases, compared to 280 and 374 under Ford and Carter. However, it ruled against unions in 35 cases, compared to 47 and 36 under Ford and Carter.

Unemployment and Job Training

Although unemployment has dropped from 10.7%—the highest since 1940—to the present 7.5%, this still represents a higher level than during the Carter Administration. The reduction occurred as a result of the cyclical economic recovery. Reagan has shown little sympathy for the unemployed. At a time when there were more jobless Americans than at any other time In over 40 years, Reagan cut the budget for unemployment Insurance by 7 percent, about $7.7 billion. He also cut overall job training and employment programs by 60 percent during his first three years in office, transferring $25 billion away from these programs between 1982 and 1985. He cut:

- General Employment and Training by 35%.

- Public Service Employment by 99%.

- Work Incentive Program by 33%.

- Jobs for Economically Disadvantaged Youth by 14%.

He dismantled the Young Adult Conservation Corps and the Youth Conservation Corps, two highly successful programs dealing with conservation projects on public lands. He attempted to abolish the separate youth programs in CETA (Comprehensive Employment and Training Act) and to abolish the Summer Youth Employment Program.

If Reagan’s 1985 budget prevails, the major programs of CETA and its successor, the Job Training Partnership Act (JTPA) will have had their funding cut by 56% between 1980 and 1985.

Minorities endure higher levels of unemployment. In 1983, unemployment for Hispanics averaged 15%, one-and-a-half times the national average. For Hispanic teenagers, the rate is triple the national average. The gap between unemployment levels of blacks and whites Is increasing. In 1981 there was an 8.6% difference; at the end of 1983, it was 11 percent. The unemployment level for black teenagers in some urban centers is 80 percent. Half the participants in the gutted CETA and JTPA programs, however, are non-white.

Human Services

Women, children, the elderly, minorities, and the working poor are the groups hardest hit by Reagan’s shifts in spending priorities. Today about 34 million people live below the poverty line, defined as an average annual income of $9,860 for a family of four. This represents 15% of the American population, the highest level of poverty in 17 years. In a single year, from 1981 to 1982, 2.6 million people fell below the poverty line. The poverty rate for Hispanic Americans is 30%, double the national average and up 15% since Reagan was elected. More than one-third of all female-headed households live in poverty. Over three million more children today live in poverty than in 1979, and they continue to fall into the poverty zone at a rate of 3,000 per day. Almost half of all black children and one out of six white children live in poverty.

Said President Reagan in June 1984: “Our tax policies have been more beneficial to (poor people) than to anyone else.” This is simply not true: the federal tax burden for low-wage earners has ballooned under this administration. A family of four at the poverty line paid 5.5% of its income in federal income and payroll taxes when Carter left the White House; today, that tax bite has virtually doubled. Moreover, families earning far less than a poverty-level income generally paid no federal income tax prior to 1981; now, a family of six pays taxes, even if its income is $4,000 below the poverty line.

Reagan’s cuts in domestic discretionary spending have been disproportionately aimed at low-income programs. This combined with the recession has dealt a double blow to the poor. Yet Reagan said in June 1984: “We are helping more people and paying more money than ever In the history of this country on social programs.” The facts say otherwise: funding for many programs aimed at poor people, including compensatory education, subsidized housing, and employment and job training programs, has dropped substantially in absolute dollar terms since 1981. When inflation and unemployment are taken into account, total spending on all programs for the poor has been cut by nearly one-sixth, with community support services and child nutrition among the biggest losers.

According to a study by the Congressional Budget Office, a non-partisan research agency, spending for human services for the poor in fiscal years 1982-85 will be $110 billion less than it would have been without the Reagan cuts, and the figure would be close to $140-$150 billion had not Congress resisted many of the cuts. These cuts are summarized by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) as follows:

- Retirement and disability programs (Social Security, civil service retirement, veterans’ pensions, and compensation and supplemental security programs) CUT $26.8 BILLION.

- Other income security programs (unemployment insurance, welfare, food stamps, child and maternal nutrition, housing aid and home heating assistance) CUT $27.1 BILLION.

- Health programs (Medicare, Medicaid and other health care services) CUT $18.5 BILLION.

- Employment and training programs (Job Corps, public service employment, work incentives, general employment and training) CUT $25 BILLION.

- Social Service programs (social service block grants, community service block grants, and veterans’ readjusted benefits) CUT $4.6 BILLION.

- Education programs (compensatory and vocational education, Head Start, guaranteed student loans and other student aid) CUT $9.1 BILLION.

Although some effort was made to paint these cuts as reforms, in general, they were made simply to save money. The CBO study says that about 40% of the “savings” will come out of benefits to households with annual incomes of $10,000 or less and 70% from families with Incomes of $20,000 or less. Reagan’s first budget proposed to take benefits of some kind from between 20 million and 25 million people who live just above the poverty line. In dollars adjusted for inflation, in his first two years, Reagan tried to cut federal aid to the needy almost in half, by 45 percent and did cut it by 28%.

According to the Children’s Defense Fund, Reagan’s cuts through fiscal year 1984 mean that the poorest and most vulnerable children in America will have lost $1 in every $6 spent on them before Reagan took office. Because military spending has been so drastically increased, overall federal spending continues to grow and the deficit to enlarge. Carter’s last budget was $664 billion; Reagan’s fiscal year 1985 budget is $925 billion. In fact, when figures published by the Republican National Committee are adjusted for inflation, they show that Reagan has not even reduced the rate of increase in federal spending.

How did Reagan do this? For years he has told tales of welfare queens and unemployment bums to arouse public indignation and said private charities ought to pick up the slack, despite protests from the leaders of these charities that they could never keep up. Reagan has targeted the most helpless: poor people make poor lobbyists.

Social Security

More than 30 million older or disabled Americans receive benefits from the Social Security system, and another 100 million workers are expecting benefits when they retire. Though he now denies it, Reagan has for years advocated that Social Security become voluntary and need-based, which would effectively abolish the program. It would put the present retirement insurance system into the same vulnerable political position as welfare. As it is now, people who would balk at receiving charity depend on Social Security with equanimity, because they legitimately paid into it all of their working lives.

Before and after his 1980 campaign Reagan created a dragon and promised to slay it, claiming that the Social Security system was going bankrupt and that he would “save and strengthen it.” Scare stories filled newspapers and David Stockman solemnly stated in May 1981 that unless Congress took direct action to preserve the system, “the most devastating bankruptcy in history will occur on or about November 3, 1982.”

There was Indeed a “shortfall” in Social Security trust funds, but “bankruptcy,” which connotes going out of business so that no benefits can be paid out, was never a possibility. The shortfall was a temporary result of wages not keeping up with prices and population changes. For every $9.50 being put into Social Security trust funds via payroll taxes, $10 was being paid out in benefits. By about 1990 this problem would have corrected itself and more would have been paid in than out. Even if the Social Security trust fund, which exists to buffer fluctuations in income and outflow, were to run completely dry, the worst that could have happened would have been a delay in sending out benefits amounting to a 5% cut—not a 100% cut connoted by the word “bankruptcy.”

Many leading financial figures disagreed with Reagan’s gloomy forecasts: Robert A. Beck, chairman of the Prudential Insurance Company, said in June 1982: “I don’t know of any reasonable study that didn’t conclude that the system is basically sound.” A half-dozen changes to fix the short-term problem were advocated by both Republicans and Democrats in Congress, including putting in some funds from general revenues, taxing benefits Issued to those over a certain Income level and dedicating those revenues to the system, and making scheduled increases in the payroll tax come sooner.

Instead, Reagan insisted on cutting benefits and proposed on May 12, 1981, to cut benefits by 22% over the long-term, including a one-third cut in benefits for the disabled. In a television appearance two months later he assured listeners that “I will not stand by and see those of you who are dependent on Social Security deprived of your benefits,” without mentioning that those who would become dependent on Social Security the following year would not receive their full benefits under his proposals. With relative ease, he convinced Congress to eliminate minimum benefits and college student benefits. His May 12 proposals combined with other budget changes in Social Security came to total cuts of $280 billion by 1990—so much that surpluses in the trust funds would have soon allowed a cut in the payroll taxes that fund the system. Some claim this is his ultimate goal.

Meanwhile, the Reagan Administration cracked down on enforcement of eligibility requirements for disability benefits and threw 42% of the cases investigated—485,000 recipients—off the rolls. The mentally ill were particularly targeted: after studying 40 cases in which mentally ill persons had been cut off, the General Accounting Office concluded that 27 of them could not work in a competitive environment and more information was needed about the other thirteen before a good judgment could be made. Administrative law judges have restored benefits to nearly two-thirds of those who appealed. On April 13, 1984, fearing mounting political hot water and accusations of cruelty, the administration announced it would suspend its efforts to cut off disability benefits.

The scare tactics worked. In the fall of 1981, a Harris poll revealed that 66% of people under 45 no longer believed that the Social Security system would exist to pay them benefits in their retirement. The damage to the public’s confidence in the system so worried Democrats that they went along with the recommendations of a “bipartisan” commission (10 Republicans, five Democrats) and agreed to a $40 billion cut in benefits by 1990 in the form of a recurring six-month delay in cost-of-living adjustments. This compromise also cut early retirement benefits from 80% to 70% of full benefits, and gradually raised the age of full-time eligibility to 66 by 2009 and 67 by 2027. Payroll and self-employment taxes were increased slightly, and benefits will be taxed over a certain income threshold. Despite the compromise’s better points, Reagan’s attempts to discredit Social Security have resulted in millions receiving reduced benefits and millions more losing faith in the system.

Aid to Families With Dependent Children (AFDC)

The Republican National Committee says that aid has been “retargeted to the truly needy.” This means that millions of Americans who hold jobs and live just below or just above the poverty line have been cut from AFDC rolls or are receiving reduced benefits. AFDC was enacted in 1962 as an outgrowth of the Aid to Dependent Children provision of Social Security. In order for a family to qualify for AFDC, there must be children who are deprived of the financial support of one of their parents due to death, disability, absence from the home, or unemployment, and they must fall below a minimum needs standard. AFDC recipients are customarily eligible for Medicaid and usually eligible for food stamps. The average AFDC family size is a parent and two children. About 98% of the AFDC national caseload are women and children; about 45% are black.

Reagan has cut AFDC funding by about 13% in fiscal years 1982 to 1985, approximately $4.8 billion, affecting 725,000 families out of a caseload of 3 to 6 million. According to a 1984 General Accounting Office study, 1981 eligibility changes took 493,000 families off the AFDC rolls, saving $93 million a month out of a total AFDC budget of $1 billion a month, and others had their benefits reduced. These cuts have been made through restricted eligibility requirements—such as lowering the income ceiling—that have hit the “working poor” the hardest. An example of one of the new mandatory restrictions is counting the income of a stepparent as available to a child whether or not it is. States also have the option of counting the value of food stamps, housing subsidies, and energy assistance as income. Although Reagan says that this has helped these families reduce their dependency on welfare, the U.S. Civil Rights Commission released a study in the spring of 1983 that said that if Reagan’s “reforms” for 1984 went into effect, in 13 states welfare recipients would lose money if they went to work.

Hunger in America

After highly-publicized remarks by Ed Meese on Dec. 8, 1983, (“I don’t know of any authoritative figures that there are hungry children”) served to call attention to White House attitudes toward hunger, Reagan said he was “perplexed” by the issue and appointed a Task Force on Hunger. Their recommendations are now under review. Meanwhile, Reagan has systematically cut federal food aid and child nutrition programs again and again.

Food Stamps. The Family Nutrition Program, now widely known as the Food Stamp Program, was initiated in 1961 in the Department of Agriculture and is now in effect in all 50 states and territories. It is a wholly federal aid program, usually administered by state departments of welfare or social services, and its purpose is to battle chronic malnutrition with its accompanying physical and mental retardation. About 22 million Americans currently receive food stamps. Eligibility is tagged to the poverty level; limited assets are also required. The average gross income of food stamp households is $325 per month. About 87% of the recipients are poor and most of the others are just above the poverty line. The average food stamp benefit is now 47 cents per meal.

The food stamp program has been reduced by nearly 20% below the levels it would have attained without Reagan’s cuts. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that food stamps have been cut by about $2.4 billion since 1962. In 1983 alone it was cut by $1.3 billion, “terminating” one million people from the program, reducing aid to four million more, and making it unavailable to many of the newly poor. These cuts were made by tightening eligibility Income criteria, reducing food stamp office hours and outreach, and making the semi-annual adjustments for Inflation annual. At least 80% of the cuts were made by reducing benefits to people below the poverty line.

Even these cuts pale beside what Reagan was asking for: in 1983, his proposal would have affected 83$ of all food stamp recipients, reducing aid for 14 million people and dropping three million from the rolls entirely. Working families on food stamps would have lost $2 of every $5 in benefits, an average yearly loss of $684.

The administration boasts that more people received food stamps each month in 1983 (21.6 million) than when Reagan was elected in 1980 (20.7 million). This is due, however, to the overwhelming increase in the number of poor people, so that large numbers continued to be eligible despite tightened restrictions. In 1981, under Carter’s last budget, 22.5 million people received food stamps.

Child Nutrition Program. The School Lunch Program and the School Breakfast Program are administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and run by local school boards. The School Lunch Program serves 23 million children in over 90,000 schools; the Breakfast program, 3.4 million children in 34,000 schools. Although all school meals receive some subsidization under the program, about 80% of the federal funds in the School Lunch Program support free and reduced-price meals served to low-income children. About 90% of the children in the breakfast program are from families below the poverty line.

The Reagan Administration has cut child nutrition programs by about 28%, or $1.5, billion, between fiscal years 1982 to 1985. In fiscal 1982 alone, school lunch programs were cut by $1 billion (about 35%) and the breakfast program lost about $78 million (20%) of federal funding. Cuts were made by lowering federal subsidies per meal (increasing the price for all meals), changing income criteria for free and reduced-price meals, and changing the application procedure. As an immediate result, two million fewer children purchased school lunches, and 1.1 million fewer children received free or reduced-price lunches. The new requirements forced 2700 schools to drop out of the lunch program entirely. About 800 schools and over 400,000 children dropped out of the breakfast program. In addition, new regulations were proposed which were so nutritionally lax that ketchup and relish would have been accepted as school lunch vegetables. (Public outcry forced the administration to drop this provision.)

The Summer Food Service Program reached 1.9 million children in 1981, but only 861,000 in 1982 after a 25% cut. The Child Care program, which provides meals in numerous day care centers, was cut by 30 percent, or nearly $130 million a year.

Under the Women, Infant, and Children (WIC) program, set up in 1972 and made permanent in 1974, needy pregnant and lactating mothers and their Infants and small children up to age five who are deemed to be vulnerable to poor nutrition are given vouchers to buy foods rich in protein and other nutrients. Initially, Reagan tried to cut $224 million from the program, about 25%; Congress rejected this proposal. But about 200,000 women, infants, and children were removed from the program in 1981 and $60 million went unspent because the federal ceiling for eligibility was changed; later Congress ordered the administration to restore these benefits. In fiscal 1984, Reagan proposed dropping 600,000 people from the program, with Congress offering some resistance. 100,000 more poor pregnant women and their children lost their WIC dietary supplement.

Health

The poor’s access to health care has been greatly reduced under Reagan. When one is cut from AFDC, one is also cut from Medicaid; and nearly half a million families have been taken off the AFDC rolls since Reagan’s election. In addition, since 1981 10.7 million people have lost some or all health coverage as a result of unemployment. Health care costs are spiraling at a rate three times that of inflation. Over 10 million of the poorest children in America depend on Medicaid for checkups, medical treatments, dental care, hospital care, and drugs. Reagan wanted to cut $12 billion from Medicaid over four years; Congress approved $4 billion, a 5% cut. In the 18 months after mid-1981 almost 700,00 children lost medical coverage and the cuts in community health centers cost 725,000 people medical services.

In the spring of 1984, the General Accounting Office released a study surveying former AFDC recipients in Boston, Dallas, Milwaukee, Memphis, and Syracuse, and found that 43% to 75% had no other health insurance coverage. Between 14% to 24% reported that they had neglected a medical problem because they couldn’t afford treatment; between 27% to 48% had neglected dental health care. In Boston and Memphis, 13.3% of former AFDC recipients had been refused medical and dental treatment because they couldn’t pay.

Reagan is continuing to seek major cuts (about one-third) in the childhood vaccination programs that keep rubella, polio, and diphtheria at bay, although at present fewer than half of black preschoolers are immunized against diphtheria and only 39% against polio. In 44 states prenatal and delivery services and preventive health services for women, infants, and children were reduced.

The effects of these cuts (added to the effects of the child nutrition cuts) will be long-term and difficult to quantify, but there is already one startling indicator of their magnitude. Although the average national infant mortality rate continues to drop slightly, Infant mortality is rising in poor rural areas of Appalachia and the deep south and inner-city slums—the areas hardest hit by the cutbacks. In Detroit, the rate has climbed to 33 per 1000 live births—the same as it is in Honduras, the poorest country in Latin America. On May 24, 1984, a Harvard researcher released results of a study revealing a 46% rise in mortality for the first year of life in areas Served by five Boston neighborhood health centers in 1981 to 1982, compared to a steadily declining rate in the 1970s. Mortality in the first month of life, which had fallen 15% in those areas in 1980, increased by 58% in 1982. The study pointed a finger directly at reduced access to health care and cutbacks in Medicaid eligibility.

Other Low-Income Programs

In addition to cuts for specific programs, much less money is being made available to states in block grants for discretionary spending on social programs. In fiscal years 1982-85, the Community Service Block Grant has been cut 39% and the Social Services Block Grant by 22%.

Reagan has repeatedly attempted to eliminate the $271 million Work Incentive Program that helps mothers escape welfare.

The Legal Services Corporation, established by Nixon in 1974, provides 85 percent of the money for local legal-aid clinics for the poor. Reagan first attempted to abolish it. Then he managed to get Congress to cut its budget from $321 to $241 million a year, forcing the departure of one-fourth of the program’s lawyers and the closing of 300 field offices. He then attempted to take it over with appointees who were opposed to its existence, but Congress refused to go along.

In fiscal year 1984, low-income energy assistance was reduced 34 percent, from $2 billion to $1.3 billion, in a time of rising gas prices.

Housing

The Low Income Housing Information Service estimates that there are 3.5 million more households with incomes under $5000 a year than there are affordable places to live. A Reagan-appointed commission stated that 7.5 million low-income families need housing assistance. Yet Reagan has advocated decimating the budget for low-income housing, including halting new construction, lowering rent subsidies, and raising rents in government housing.

Budget figures in the housing sector are tricky to evaluate; overall housing spending has risen slightly, because most of this goes to middle-income lending and mortgage insurance payment and tax expenditures, especially on homeowner mortgage interest and property tax deduction. Actual outlays for lower-income programs have risen: $4.5 billion in fiscal 1980, $7.7 billion in 1983, and $10.8 billion in 1984. However, this merely represents the fulfillment of obligations created by Ford and Carter; Reagan has tried to limit future obligations to near zero.

In the fiscal year 1981, Carter’s last budget, the federal government obligated $26 billion for future spending on low-income housing. Reagan proposed the obligation of $14 billion in fiscal 1982, $8.7 billion in fiscal 1983, and a remarkable $0,515 billion in 1984—only 1.3%, allowing for inflation, of the amount obligated in President Ford’s final budget. Congress has refused to go along, giving $8.7 billion in new funding in 1982, $10.9 billion in 1983, and $10 billion in 1984—the latter a twentyfold increase over Reagan’s proposal.

Nevertheless, funds for subsidized housing for the poor have been cut 60% since 1981. Rent subsidies for the elderly, on which about one million people rely, have declined somewhat and would have been nearly halved by Reagan’s 1983 proposal. The rural poor have also been hit by budget cuts in the Farmers Home Administration from $3.7 billion to $1.1 billion.

About 2.4 million people with; incomes averaging less than $6,000 a year live and pay rent in government-subsidized housing. Reagan succeeded in raising rents from 25% to 30% of tenants’ income but failed to convince Congress to let 30% of food stamp benefits count as overall income. Reagan opposed future construction of new housing units, but under severe pressure from Congress, he acceded to a new $15.6 billion housing authorization involving more than 20,000 new units.

Reagan has often publicly sympathized with young middle-class couples who can no longer hope to own their own home because of high-interest rates, but he cut Government National Mortgage Association support for home loans by $16 billion (25%), and vetoed a Congressional bill to subsidize home mortgages with $3 billion in a five-year plan to reduce interest rates on such mortgages by up to four percentage points. The bill was championed by a Republican, Sen. Richard Lugar of Indiana, who claimed it would build 400,000 new homes and put 700,000 people back to work per billion dollars spent.

Education

Reagan initially attempted to cut federal aid to education by one-third, with larger cuts in programs like Title I, which provides compensatory education in the basic skills to disadvantaged children. His Commission on Excellence in Education recommended substantial and costly improvements in public education and a continued federal role, but Reagan’s main education initiatives have been advocating school prayer and $245 in tuition tax credits for parents with children in private schools.

Reagan originally planned to abolish the Department of Education, and he wanted federal aid to education halved by 1986. Thanks to public outrage and congressional action, the 1984 budget of $15 billion is about the same as Carter’s last one, not adjusting for inflation. In real dollars, however, federal outlays for education have dropped 14% from 1980 to 1983. The Department of Education staff has been cut by 25%, removing 2000 employees.

Several small programs have been consolidated into a block grant to the states and given a 35% cut in overall appropriation. Facing shrinking state and local revenues, most states chose to spend these funds a mile wide and an inch deep, and small, specific, and at times unpopular programs, such as desegregation aid, lost out. There has been an overall transfer of money to the West from the East and Midwest, and from urban and rural districts to suburbs.

Compensatory Education and Desegregation. Reagan believes that federal intervention has caused school deterioration. Many educators, however, credit federal programs such as Head Start, Title I, and desegregation aid with narrowing the gap in reading skills between young black and white pupils. Half of all black students in the South now attend fully Integrated schools. In 1960, only 41% of American students finished high school, but 66% had by 1980. 20% of black students graduated from high school in 1960, compared to 51% in 1980. Minorities have been closing the gap in SAT scores since 1976. Twice as many black students—nearly one million—were enrolled in college in 1981 than in 1970.

Reagan has dismantled the Emergency School Assistance Act, a modest program to aid voluntary integration, and his Justice Department has declared that it will no longer pursue cases involving busing to achieve desegregation goals. Because of Reagan’s cuts, 1.5 million children were denied the help that Title I should have given them in the 1982 and 1983 school years.

Handicapped. Hundreds of thousands of handicapped children once isolated in institutions are now in public schools because of the 1975 Education for All Handicapped Children Act. When Reagan tried to loosen regulations requiring the nation’s estimated four million handicapped children to receive a mainstream education where that is feasible, the Senate passed a resolution saying it would not go along by 93 to 4.

Bilingual Education. Although Reagan claims he is committed to bilingual education, he first proposed to abolish the Bilingual Education Program, then he reduced its funding from $161 million in the fiscal year 1981 to $138 million in the fiscal year 1982 and $95 million in 1983 and 1984. The number of students helped fell from 324,000 in 1980 to 125,000 in 1983.

Higher Education. There has been a 27% overall cut to higher education in fiscal years 1982 to 1985, affecting nearly 700,000 young people. Reagan terminated the Social Security Student Benefits program and tried every year to gut the Pell Grants system, which was started under Nixon for disadvantaged college students. Pell grants have actually been cut 13% since 1981 and would have been cut further had not Congress intervened. For 1985, he is trying a new tactic: instead of the current maximum award of $3900, low-income students could receive $3000 provided they contribute a minimum of $500 themselves—an impossibility for many students.

Reagan has also tried to decimate the Guarantee Student Loan; fee changes have in fact reduced them by about one-third. The fiscal year 1985 budget also recommends that national direct student loans, state student incentive loans, and supplemental opportunity grants receive no further federal funding.

Weslyan and other colleges have publicly announced that they are having to reject qualified applicants who cannot pay full tuition. There are signs at many colleges that fewer students from poor families are applying for admission; as state and federal support dry up, many universities and college students are experiencing dramatic hikes in tuition by as much as 15% a year. The small steps taken to Increase access to higher education for us all are being retraced.

Civil Rights

President Reagan is on record as opposing every major civil rights law, Including the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the 1965 Voting Rights Act, and the 1968 Fair Housing Law. Reagan’s civil rights stand earned him the endorsement of the Ku Klux Klan during his 1980 campaign (which he publicly rejected), Reagan made numerous attempts to weaken the 1965 Voting Rights Act when it came up for extension in 1982, shifting his position a number of times when outraged public and Congressional reaction made it clear that he would not be able to gut it as he wished. The effects of this law have been clear: between 1965 and 1980 the percentage of blacks who were registered to vote in the South increased from 29% to 57% and many more blacks held office.

Enforcement of existing civil rights legislation has dropped dramatically under Reagan. There has been a 15% cut in actual spending power for civil rights enforcement budgets and staffs in five key federal agencies. Advocating “color-blindness and neutrality,” Reagan’s Justice Department has stated that it will no longer use affirmative action principles in the hiring of federal employees, rejecting the principle of transitional favoritism to offset historic patterns of discrimination. The number of equal employment opportunity suits has declined more than 70% compared with the Carter Administration.

Carter proposed regulations to enforce the 1968 Fair Housing Law; Reagan promptly withdrew them. In 30 months the Department of Justice has filed only six new lawsuits under the Fair Housing Act. Before 1981 it had brought 20 to 32 actions a year.

In the past, Reagan supported a constitutional amendment to eliminate forced busing. The Justice Department said in 1981 that it would not require defendants in school desegregation cases to prove that their segregation was unintentional, thus making it harder to prosecute. When in 1983 a federal court ordered the Justice Department to begin proceedings against Alabama officials on a charge of racial segregation in Alabama higher education, it was the first new education case in two-and-a-half years.

On June 13, 1983, the U.S. Civil Rights Commission said it was “disappointed and concerned” by the President’s failure to put more women, blacks, and Hispanics in high-level government jobs. As of October 1980, 16.1% of Carter’s judicial appointments were blacks; only 2.5% of the 121 federal judges named by Reagan were black. Carter appointed 110 Hispanics to full-time positions in government; Reagan, 35. No Hispanic has been appointed to a position requiring Senate confirmation.

The U.S. Senate rebuffed Reagan’s attempt to put the U.S. Civil Rights Commission, an independent watchdog created by Eisenhower, out of business by replacing the Commission with his own appointees. Then, in the fall of 1983, Reagan suddenly fired the three Democrats on it who had been appointed by previous administrations and replaced them with three thoughtful critics of affirmative action. He also arranged that two outspoken civil rights activists—both women and both Republicans—would be denied reappointment.

On January 8, 1982, the administration suddenly announced the reversal of an 11-year-old IRS policy denying federal tax exemptions to schools that discriminate on the basis of race. This meant that more than 100 such schools, including Bob Jones University, which expels students for inter-racial marriage, and Goldsboro Christian School, which bars blacks because God separated the races, would be exempt from paying unemployment, Social Security, and federal income taxes, and their benefactors could deduct their contributions. Such an exemption is in effect a matching grant from the Treasury. In May 1983, in an 8-to-1 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the IRS’s policy of denying their exemptions was entirely legal, Congress refused to overturn the policy, and the administration appeared to back off the issue.

Although minority groups have stopped short of calling Reagan a bigot, several have suggested Reagan’s spending cuts are an attack not on the programs per se but on the people they serve. Says the National Urban League: “The bald truth is that not only has movement toward narrowing the socio-economic gap that separates black and white Americans come to a dead halt, retrenchment has set in and Blacks are actually regressing.” The black unemployment rate in 1982 was 18.9%, more than twice the white rate, and between January 1981 and August 1983 the black unemployment rate went from 13% to 21% (for black teenagers, 37% to 50.6%). In 1982, median black family Income was 55% of median white family Income, $13.598 compared to $24,593—an income gap larger than any in the 1970s or early 1980s.

Women

Reagan actively worked to defeat the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) and his party’s refusal to support the ERA in its 1980 platform broke a long tradition of bipartisan support.

Reagan also is working toward a constitutional amendment that would make abortion illegal. The next president may have the opportunity to appoint between three and six justices to the Supreme Court and thus Influence rulings on reproductive rights for several decades. Commenting on how women have been hit by Reagan’s social program cuts, the National Organization for Women (NOW) says: “It is perfectly clear that Ronald Reagan’s great concern for fetuses does not extend to already born children—and certainly not to their families.” Nearly 60% of children in female-headed households live in poverty. 72% of the elderly poor are women; Social Security, which Reagan tried to cut by 22%, is the only significant source of support for 90% of these women.

Women currently make 62¢ for every dollar men make. Women with college degrees and full-time jobs bring home less money, on average than men who never finished high school. In 1982 women were the sole support of more than 9.4 million households. In 1960, 23.3 million women were workers; in June 1982, 47.7 million were workers, comprising 43% of the labor force. But jobs were held at the lowest end of the pay scale: in 1981, 8 of 10 clerical workers, 6 of 10 salespeople, and 7 of 10 teachers were women, while only 14% of lawyers, 14% of doctors, and 4% of engineers were women.

Reagan has refused to effectively enforce federal employment discrimination regulations; the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission has sharply reduced litigation of discrimination cases. Reagan’s Justice Department recently argued in a Supreme Court case for drastically limiting the use of Title IX, which prohibits sex discrimination in education; many schools can once again arbitrarily limit the number of women they admit.

Reagan has appointed one-third fewer women than his predecessor to full-time positions in government—very few of whom were minority women. Despite the appointments of Elizabeth Dole, Margaret Heckler, Jeane Kirkpatrick, and Sandra Day O’Connor, Reagan has overall appointed 19% fewer women to top-level jobs than did Carter.

Civil Liberties

According to Ira Glasser, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), the Reagan Administration “seems to regard the restriction of information as a central strategy of government.”

The Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) guarantees a citizen the right to have access to non-classified government Information. In Britain, where there is no FOIA, Individuals and organizations spend tremendous amounts of time and effort simply obtaining leaked copies of documents the government does not wish to disclose; as a result of FOIA, Americans have immediate access, and rarely need to press their case in court. In October 1981, the administration attempted to gut the FOIA through a “reform” bill that would have placed numerous new restrictions on information requests, including increasing request fees, allowing agencies “stall time,” requiring agencies to deny access to any “business information” if its disclosure “could” Impair the “legitimate business interests” of any person, and many other weakening clauses. The bill has not succeeded. On Jan. 7, 1983, the administration unsuccessfully attempted to override the 1974 fee waiver provision, which said that documents were to be furnished without charge or at a reduced rate when the release of the information was in the public interest.

In 1982 Reagan Issued an Executive Order on Classification that makes it far easier to classify information. There have also been major efforts to restrict and censor the communication of unclassified scientific information to scientists in other countries.

The administration has also proposed a “gag rule” that would require all federal employees that at any time had access to “sensitive compartmental information” to submit all future writings, even after leaving government service, for pre-publication review. This would mean, for example, that a president could sensor his predecessors’ memoirs.

In January 1983, the U.S. Department of Justice labeled three Canadian films—the Academy-award-winning film “If You Love This Planet,” featuring anti-nuclear activist Helen Caldicott, and two films on acid rain—as “political propaganda” under a provision of the Foreign Agents Registration Act. This meant the National Film Board of Canada was required to label the films with a statement that it is a “foreign agent” and submit the names of theaters and organizations showing the films and the number of people in attendance. Widespread defiance of these rules and .public ridicule ensued. While the films enjoyed notoriety in some areas, distribution in other areas suffered.

Perhaps most disturbing of all, the State Department has begun denying entrance visas on the basis of political affiliation in order to keep out points of view that they do not want Americans to hear. Here are two examples of many: approximately 320 delegates from Japan, Australia, Africa, Canada, and Europe seeking to attend the U.N. Special Session on Disarmament in June 1982 were denied visas. On March 3, 1983, the State Department refused to grant a visa to Hortensia Busse de Allende, widow of the slain Chilean president, under the authority of the Infamous Walter-McCarran Act (a vestige of the McCarthy era) because “her entry into the U.S. to make various public appearances and speeches has been determined to be prejudicial to U.S. Interests because she is a highly placed official in the World Peace Council, which is affiliated with the Soviet Union, both ideologically and financially.” Mrs. Allende had been invited to visit California for two weeks by the Northern California Ecumenical Council, the Catholic Archdiocese of San Francisco, and Stanford University. It would not have been her first visit to the United States.

Crime

Although Reagan often speaks of “getting tough on crime,” he sought budget cuts in the FBI, the Drug Enforcement Administration, and the Customs Service of between 6% and 12%. Each year, the administration has “zero-funded” the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, although 17.2% of all serious crimes are committed by juveniles, who then “graduate” to criminal careers as adults. By 1984, the administration had cut drug and alcohol prevention and treatment programs by 25% over what was spent in 1980.

The administration has cracked down on drug traffic in southern Florida, and the government has seized nearly 12,500 pounds of cocaine in 1982—more than three times the amount captured in 1981. There is some evidence, however, that this has merely shifted drug traffic to other corridors, such as the Gulf of Mexico and the Northeast.

Reagan has formally proposed doing away with the exclusionary rule, a law which says that evidence found during an illegal search cannot be used in a criminal trial. The administration also wants to empower judges to jail accused people without bail and without trial unless the accused can prove he or she would not commit a crime if released on bail—thus changing the presumption of innocence until proven guilty into guilty until proven innocent.

Attorney General William Smith asked Congress to eliminate the insanity defense. Reagan suggested the law could be changed from “not guilty by reason of insanity, to guilty but insane.”

Although John Hinckley bought his cheap pistol in a Dallas pawn-shop (Texas lacks gun registration requirements), Reagan is still firmly opposed to the registration of firearms. In 1983, 21,000 people were victims of murder; 43% were killed by handguns. Reagan has also fought against a Congressional bill to outlaw man-maiming and armor-piercing “Cop-killer” ammunition.

Regulations and Safety

Under the rubric of “regulatory relief,” Reagan has pressed a policy of “getting government off our backs.” Rules and regulations, in general, restrict what business can do, and therefore, are “costly and unnecessary” in Reagan’s view; the administration points with pride to the reduction in the size of the Federal Register, which prints federal rules and regulations. But while the elimination of “rules and regulations” sounds vaguely appealing, the specific rules and regulations being repealed are those designed to protect the environment, increase auto safety, enable the elderly to travel by bus, regulate worker exposure to toxic chemicals, and many others.

Reagan has proposed a “regulatory reform” bill that would require agencies to prove that the economic benefits of a major regulation will outweigh its costs, even though costs are simple to calculate while benefits, such as better health, are less easily quantified. For example, the federal standard for cribs has reduced by half the number of infant deaths from strangulation; studies show that between 1973 and 1979, child-resistant bottle caps saved the lives of 200 to 300 children under the age of five. The regulatory reform bill is being opposed by the entire public interest community.

OSHA. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration was once termed by Reagan as “the most pernicious of the watchdog agencies.” In 1981 OSHA inspections dropped 21% and follow-up inspections dropped 72%. Between the end of 1980 and mid-1983, the number of workers covered by OSHA inspections dropped 45% (1.5 million workers). Serious health and safety violations uncovered by OSHA fell 47%, willful violations were down 92%, and repeat violations dropped 64%. What inspections remained tended to be “paper” inspections—lookings’ at business records without inspecting actual working conditions. According to the Department of Labor, 100,000 workers die each year as a result of on-the-job exposure to toxic substances. OSHA has failed to tighten the standard for benzene, even though the current standard is estimated to result in risks of 1400 to 1700 leukemia deaths for every 100,000 exposed workers.

The administration held up efforts to tighten the asbestos standard for almost three years despite evidence that thousands of workers exposed at current standards would die of asbestos-related cancer. The new standard set in November 1983 is still five times higher than that recommended by OSHA in 1980.

Procedures for setting workplace standards for other toxic or carcinogenic chemicals—cadmium, beryllium, nickel, chromium, formaldehyde, ethylene dibromide, and ethylene oxide—have been delayed or halted. However, much time has been found to “review* existing standards, such as that for cotton dust, lead, and radiation, in order to try to weaken them.

A number of states have passed “right to know” laws guaranteeing a worker’s right to be informed of his or her workplace exposure to hazardous substances. OSHA passed a much weaker set of rules and is trying to have them override the state rules; three Northeastern states are currently suing to keep OSHA from substituting its rules for the tougher and more specified laws they have on the books.

Mine Safety. About 216,000 miners work in about 2,100 deep mines and 2,800 surface mines in the U.S. Before 1952, between 500 and 2000 U.S. miners died in mine accidents every year. Federal Inspections and sanctions began that year and annual deaths dropped to about 100 per year. Reagan reduced the number of Inspectors by 10%, there were 5000 fewer inspections in 1981 than the year before, minimum fines for safety violations by mine operators were decreased, and deaths increased to 155. The administration then restored the Mine Safety and Health Administration budget.

Auto Safety. Each year 50,000 Americans die in automobile accidents. Federal rules had required automatic passive restraints (in effect, either airbags or automatically locking seat belts) in new full-size cars in 1981, mid-size cars in 1982, and compacts in 1983. In spring 1981 Reagan announced a one-year delay in these and other auto-safety regulations despite government and Independent estimates that passive restraints would prevent 9,000 deaths and 65,000 serious injuries per year. Later, the director of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration rescinded the rules altogether. A federal court threw out his action as arbitrary and capricious and ordered that all cars sold after September 1983 be equipped with airbags or automatic seat belts.

Environment and Energy

Reagan’s lack of sensitivity to environmental concerns has become almost legendary, and his appointments in this area have been vociferously criticized. All three of his Cabinet-level appointees—James Watt at Interior Department, Anne Gorsuch-Burford at the Environmental Protection Agency, and James Edwards at the Department of Energy—have been replaced with less controversial figures, but the effects of severe budget cuts and internal reorganizations will linger for years. Faced with an array of new environmental legislation passed in the 1970s, Reagan chose to strip enforcement of those laws and weaken administrative rules that put them into effect. Although public protest, Congress, and numerous lawsuits brought by environmental groups have ameliorated these changes, the damage may be lasting.

The fate of the Council of Environmental Quality (CEQ), a modest-sized watchdog agency created by President Nixon in 1970, seems to demonstrate Reagan’s priorities. With its budget cut by two-thirds and its entire professional staff fired, the CEQ is a shadow of its former self and no longer publishes its annual reports on the nation’s environmental quality.

Pollution Control

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is responsible for administering and enforcing major pollution laws and for regulating toxic chemicals. The EPA suffered major budget cuts and purges of experienced professionals under Anne Gorsuch-Burford, who resigned in 1983 after a scandal (“Sewergate”) involving favoritism to polluters. Reagan accepted her resignation reluctantly, praised her for the “fine job” she had done at the EPA, and blamed the media for her resignation.

The fiscal year 1984 budget calls for 22% fewer staff and 43% less money for the EPA than in Carter’s fiscal year 1981 budget, although a study by a group called SAVE EPA calculates that new laws that add to the EPA’s workload require a 43% increase in personnel and a 69% jump in funds to do the job right. The EPA’s research and development funding has been cut in half, although “lack of sufficient research” is often cited by the administration as an excuse for delaying action on such problems as acid rain. While the EPA claims it has given power back to the states for enforcing environmental laws, it has cut grants for such enforcement by 40%.

Shortly after taking office Reagan issued an Executive Order which gave the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) de facto veto power over environmental regulations. It has exercised this over several dozen rules; for example, it suspended pretreatment regulations for industrial pollution, delayed three new air pollution rules, and delayed the labeling of toxic substances in the workplace. The OMB has tended to exempt rules from review if they relax rather than increase the burden on industry.

Air Pollution. The 1970 Clean Air Act has resulted in measurable progress toward healthier air, though when Reagan took office, 140 million Americans still lived in areas where air pollution violated health standards during some part of the year. Reagan has cut the EPA’s air quality staff by 30% and its budget by 40% since the fiscal year 1981. The EPA has been slow to issue new regulations that are required by the Clean Air Act, such as clean-up requirements for diesel cars and trucks and for heavy-duty gasoline-powered trucks. It has delayed setting emissions standards for 30 suspected toxic pollutants—12 of which have been declared carcinogens by the National Toxicology Program.

The EPA has also weakened or abolished many existing regulations. It increased the allowable emissions of sulfur dioxides from power plants by a million-and-a-half tons per year, despite a consensus of scientific opinion that a decrease of 12 million tons per year is essential to limit acid rain. Although Reagan described acid rain as his highest priority when he appointed William Ruckelshaus to be the EPA Administrator, he allowed the Office of Management and Budget director David Stockman to shoot down Ruckelshaus’ acid rain program—which was a modest one-third the size recommended by the National Academy of Sciences.

In its first two years under Reagan, the EPA referred an average of 65% fewer cases of violations of the Clean Air Act to the Justice Department for enforcement, compared to I980.

The administration has supported congressional proposals to weaken the Clean Air Act, including:

- Allowing deadlines for attaining health standards to slip until 1993.

- Weakening auto emissions standards to allow a doubling of nitrogen oxide and carbon monoxide emissions.

- Eliminating the requirements that in polluted areas new sources of pollution use state-of-the-art pollution controls.

- Allowing greatly increased pollution in relatively pristine areas such as in National Parks.

These proposals have been stalled, and the Administration is concentrating instead on stopping amendments to the Clean Air Act that strengthen it in two areas: acid rain and hazardous pollutants.

Water Pollution. The Reagan EPA has also slowed down progress toward achieving the goals of the 1972 Clean Water Act. The water quality staff has been reduced by 38% and its funding by 57% since 1981 levels. The EPA has sought to weaken or evade responsibility for protecting groundwater from hazardous wastes and identifying toxic water pollutants. Enforcement actions against wastewater dischargers have fallen off from 697 in 1980 to 410 in 1982. A December report by the General Accounting Office found that 82% of the 53 major wastewater dischargers surveyed had violated their permits, and nearly a third of the violators were in “significant non-compliance.” The study blamed it on the severe budget cuts and dropoff in the EPA’s enforcement.

Reagan has backed off from some early proposals to drastically weaken the nation’s clean water law. However, the administration continues to fight strengthening amendments to the Clean Water Act proposed in Congress, including ones that:

- Increase federal funds for municipal sewage treatment.

- Establish a program to deal with “non-point” sources of water pollution (such as agricultural run-off).

- Further protect groundwater from contamination.

Toxic Chemicals. Toxic chemicals are poisons. There are over 55,000 chemicals now in commercial use in the United States and 10 to 20 new chemical compounds are introduced into commerce every week. The 1976 Toxic Substances Control Act requires the EPA to gather information and test data and if necessary restrict the use of toxic chemicals before they are placed on the market. It also requires the EPA to review all chemicals in use to regulate those that pose unreasonable risks.

Reagan has stalled the slow progress that had been made toward these goals. Staff for this task has been cut 22% and the budget by 31% since 1981. Roughly, 2000 priority suspect chemicals await review, with 100 added to this list each year. No rules have been issued on the conducting of safety tests for new chemicals; Ruckelshaus advocates “voluntary testing” by companies. The EPA has also failed to meet deadlines for the testing of dozens of chemicals deemed by a federal interagency panel to be suspected of causing cancer, genetic damage, and birth defects. It has put off regulating DEHP and formaldehyde, two widely used chemicals, despite staff recommendations that these deserve “priority assessments.”

Hazardous Wastes. The Reagan Administration has failed, particularly in its first two years, to carry out the nation’s hazardous waste law. It dragged its feet on cleanup, used toxic dump cleanup “superfund” money to aid Republican political candidates and made “sweetheart deals” allowing the companies responsible for the wastes to escape from most of the costs of clean-up. The resulting national scandal led to the resignation of the EPA’s top leadership in 1983 and the criminal conviction of toxic wastes chief Rita Lavelle for perjury before Congress. Under Ruckelshaus, these policies are improving slowly.

Of the nation’s toxic waste dumps, 2,000 are estimated to pose a serious health hazard. Cleanup has been completed at only six sites since Reagan took office. Litigation against violators to recover Superfund money has been hesitant and many opportunities to recover taxpayers’ money have been lost. There is still no policy regarding public input in clean-up decisions.

The cheapest way to avoid cleaning up hazardous waste dumps is to prevent inadequate dumping in the first place. The 1976 Resources Conservation and Recovery Act provides for “cradle to grave” management of wastes, but the staff for implementing these regulations at the EPA has been cut 37% and the budget by 32%. The administration has resisted Congressional efforts to close loopholes in RCRA and attempted to suspend rules designed to control the incineration and storage of wastes at pits, ponds, and lagoons. Burford suspended the ban against the burial of liquid wastes in drums, but the ban was soon restored after public outcry.

Pesticides and Herbicides. There are now over 1,500 chemical compounds which kill insects, weeds, and other “pests.” About two billion pounds of these chemicals are applied a year. The law requires the EPA to evaluate the safety of each pesticide compound and ban it if it poses substantial risks to human health or to the environment. To conduct research and consider regulation on at least 600 generic groups of pesticides will be a complex task requiring about 15 years to complete; however, Reagan has slowed this down considerably by cutting staff in this area by 25% and funding by 48% below 1981 levels. At this rate, the review could take up to 40 years.

Reagan failed to move quickly to ban EDB despite a National Cancer Institute study showing that it causes cancer in laboratory animals and several other studies indicating that it could contaminate groundwater and that residues on bread and grain could be harmful to humans. By 1980, the Carter Administration was poised to cancel most uses of EDB. But thanks to hard lobbying by large agribusiness interests, Reagan postponed regulatory action until 1985. In 1983, traces of EDB were found in groundwater and in over 100 grocery products, prompting several states to recall products from supermarket shelves. As much as 50% of the nation’s wheat, corn, oats, rice, barley, rye, and sorghum have been treated with EDB.

The Reagan Administration has joined in legislative efforts to weaken federal pesticide laws by limiting the access of independent scientists to critical health and safety data and by forbidding states such as California to write stronger regulations than those proposed by the federal EPA. The administration has also opposed efforts to strengthen current pesticide law.

Natural Resources and Land Use

The Interior Department, responsible for the management of the nation’s public lands, was headed for nearly 30 months by the flamboyant James Watt, whose outspoken disdain for the environmental movement provoked 1.1 million signatures on a Sierra Club petition calling for his resignation within six months of his taking office. Likening conservation organizations to “Nazis,” Watt called them “left-wing cults which seek to bring down the type of government I believe in.” He told Michael McCloskey, executive director of the Sierra Club: “We’re going to get things fixed here, and you guys are never going to get it unfixed when you get in.” It is important to remember that President Reagan supported Watt every step of the way, and he accepted Watt’s resignation reluctantly when his Interior Secretary’s insults to minorities began to cause him acute political damage.

Public Lands. Though the number of visitors to National Parks continues to increase, Reagan has not asked Congress for one penny to buy new parklands. He has opposed buying parkland already authorized by Congress and helping states or cities to purchase their own parks. By the end of 1983, Reagan had spent only half of the $168 million designated by Congress for parkland acquisition that year. The Interior Department has concentrated spending on roads, sewers and facilities for visitors rather than on protecting natural areas.

The Reagan Administration has proposed development near parks and in wilderness areas. It has:

- Supported a coal strip-mining project only a few miles from a viewpoint in Bryce Canyon National Park, in plain view of the 400,000 people who visit the spot each year.

- Proposed coal-lease sales in New Mexico which will damage or destroy archeological artifacts in the nearby Chaco Culture National Historical Park, which date from prehistoric to recent Indian cultures.

- Considered putting a high-level nuclear waste dump within a mile of Canyonlands National Park, close to the Colorado River.