Unpublished, February 1989

Feb. 9, 1989

A few moments before I stepped on the plane, I asked David: “Is there anything you would like me to tell the whales and the penguins?”

He thought for a moment. “Tell them to have hope,” he said at last.

Pause… “OK. Anything else?”

He thought some more, “Tell them that if there’s anything they would like to tell us, they should just let us know.”

We’re here, and ready to listen. And to have hope: yes, that’s the most important of all.

Feb. 10—Santiago

In the few moments before sleep, on the darkened plane, I felt how south we were moving—felt us speeding into a new quadrant of the planet—and heard the words from the guidebook: “Antarctica has yet to be permanently inhabited.” I felt the presence of all of those whales and dolphins, seals and birds, krill and fish—especially the cetaceans, with their large and mysterious brains, their playful and unknown purposes, swimming and leaping and raising children and singing to one another, in a kind of cetacean Eden still largely innocent of humankind. The air is still pellucid, the water pure, the sunrises unsmudged and bold—the silence in the wind unmarred. Is this continent, this pole, a stronghold for Gaia—for an intelligence of harmony, a memory of innocence? Do the whales and dolphins know, through intuition, through stories and reports from afar, through their own senses, that the planet is in danger? Do they worry? Do they see themselves as guardians and protectors of a kind of wisdom? Are they doing what they can to help?

The plane flew south, toward them, splitting wide the silence, full of questions. It is not a place like most others. It is a journey to a holy land. If God and Goddess have been chased down from the mountains, banished from the groves, exiled from the seas, wrung from the soils and scraped from the deserts and entombed within the cities—if it must be a slow and active process to coax holiness back into most of the world, to draw it from the roots and plead for it from the skies—calling out, “It’s okay now! It’s safe! We will not dishonor you again!” Here, in vastness, in wholeness, the exile never was. The earth is still in that always longed-for condition of “before”—before the rapes and ravagings, before the big trees were cut, the rivers turned muddy, the meadows scarred. This land must still, almost, be whole and holy. Yes, the pollution reaches even there, the global warming, the ozone hole, the depletion and massacre of the whales, the institutions of dirty little fishing ships crawling on the face of beauty, but it is not a pitifully small or isolated patch of memory surrounded by loss. It is memory itself, full, proud, complete. If Gaia is being weakened, is ill, this must still be one of her healthiest and strongest lands—and, I keep thinking, where a reservoir of consciousness yet lives and grows.

Chili, what did I know about Chili, before today? Pablo Neruda, in a few translated poems…the killing of Allende…Nixon…Pepsico…the novelist Isabel Allende…my friend Monica’s birthplace…The woman whose son had been tortured, speaking calmly and with such serene power to 200 befuddled Cantabrigians in Faneuil Hall for Amnesty International. The petition campaign of East-West democracy…the mother’s quilt project…The little Chilian boy whose visit to Artek earned him prison, and whose release after a protest campaign empowered the young singing group in Leningrad.

So, and as always with first visits to countries of political repression, the initial impression is of bewildering normality. Energetic young men in oxford shirts and ties striding the sidewalks. Children wriggling in fountains. Young couples entwined on the grass. Shops, metro, older men hosing down gardens, new cars filling the wide paved streets, ice cream vendors, an organ grinder producing a fluttering of pan-pipes, jewelers crafting earrings, a sidewalk café filled with conversations, a mother with a nursing baby and three-year-old daughter begging with a cup at the subway exit. Did Hitler’s Germany also appear “normal?” …Stalin’s Russia? …does Khomeini’s Iran? What are the sidewalks like in Albania? It makes me wonder at resilience, at resourcefulness, and also at the distance there seems to be between political freedom and involvement, and the apparent ease with which people still pursue, often successfully, their small joys and fulfillments and days.

Overall, California—San Jose or perhaps even LA—with a touch of European class, and an overall slightly darker shading of hair and skin. But the ice plants lining freeways…the layered apartment…the gap between rich and poor…the presence of multinational corporations…the seedy pastel stucco shopfronts, watered strips of green between streets, smog and diesel mixed with traces of flowering trees, of frangipani and bottlebrush…the casual, fashionable dress and sunglasses and self-absorption the people wear. It is California moved south, complete with Shell stations and Sheratons. Somewhere—not here—barrios ring their central, casual affluence and normality. I saw them in the wary, not quite truthful returns of my friendly “Hola!” to the men watering plants with long city hoses. At dinner, one of the alumni men said their tour bus had been given the finger. Yet overall there is a gentleness, a relaxed and forgiving and kind quality within these people, a combination of fire and water, passion and reflection, that I can imagine someday learning enough to term distinctively South American. They too round out and balance the medicine wheel of our human family. With them, I see myself and nearly everyone I know as definitely “northism temperate” in culture and lifestyle. How gently and pervasively the very winds and temperature, sun and soil of a particular region of our earth imbue the people who live there with the personality of the land itself!

Best of all was stumbling into the little thatched roof market, and finding, amidst the earrings and windchimes and pottery, the hints of a counterculture of an alternative politics. Small printed bookmarkers quoting Neruda, John Lennon, Violetta Parra (a poet-singer), Ernesto Cardenal and Walt Whitman were for sale, as were posters of Allende and buttons with, among others, Che Guevara. Lennon and Neruda seemed to be the most important symbols available to counteract the huge Pepsi and Xerox signs. There were even translations of Gorbachev’s speeches in one small bookstore. It was encouraging to see these things, unmolested. I know nothing about today’s situation, but I sensed a turn for the better, a weakening of the old guard, in the magazine cover stories linking Pinochet to some old ex-Nazi.

A glimpse—a feeling—a good centering run, yoga, and swim; but I am ready for the air to turn cold again.

Feb. 11, 1989

A patchwork day—bits and pieces—steadily threading together toward the end.

The utter domination of the U.S. culturally and politically is almost difficult to comprehend. Is it this way all over the Third World? I expected the Xerox and Pepsi billboards, the “Roger Rabbit” movie and Izod shirts, but American pop music in the flea market? A “world” section in the main newspaper entirely composed of op-eds and articles from The L.A. Times, The Washington Post and The New York Times? Some teenaged girls riding one of their wild, open-air, free enterprise buses gestured and laughed at our bus—perhaps obscenely. When I asked the Punta Arenas guide about Violetta Parra, his face turned rapt and sentimental. A fabulous artisan and artist in ceramic, wool, paints; the very best Chilean folksinger and composer. Her death—by suicide—two years ago was commemorated last week. “There was only one little problem,” he said ruefully, “She was a Communist.” Do you like the present government? “I am in opposition to this government,” he said, “but I am not a Communist.” The rifts still run deep and volatile here, as the Santiago tour guide revealed… our very interesting history of Chili ended just after the 1973 coup! The Punta Arenas man, a gentle soul, teaches mentally retarded children between the ages of three and six. As Annie Dillard says, Punta Arenas is out of the way—of what?”

Only as I stand at the bow and stared into the fading light and dark clouds above the channel did it finally seem real. This is my first voyage, I realized; tonight will be the first time I’ve ever slept on a boat on the sea. Already, the stars are soft in their brilliance; the water so clear, so unmarred, the air so fresh…and so silent. This is, indeed, a different land. Before casting off, I stood at the stern and waved and smiled at the guys unwrapping the lines and hanging out on the fishing boats. Pleased and startled, they flashed toothy smiles in return. Namaste—“that which is God in me honors that which is God in you.” There are many kinds on this ship, but already those of us under 40 are discovering one another and making friends. I like Keith, who lived through Berkeley in the early 70s and narrowly escaped ‘Nam, who hopes to raise kids on a piece of sane land 250 miles northeast of Seattle, on the east side of the Cascades. There are many people here who have cruised in the Soviet Union, and hardly anyone who knows anything about the country.

Already Chile, a brief dream, seems distant—my first real look at “imperialism”, as an adult. At any rate—the people we saw were, as Mom put it, “well-dressed and well-groomed.” Is this the reward for being good? The way masters reward and groom and feed and house their favorite dogs and horses—the good life of dependency? The happy serfs. Something like that. But, I think, an unusually high level of awareness, of literacy and education and caring; it’s hard to imagine what they have gone through, or that it could possibly last much longer.

Feb. 12—Beagle Channel

So, it can stay like this—soft haunting rain, fog blurring the mountains’ edges, calm wide waters—the whole trip, if it wishes. The decks are clean and empty and free. I sit and look, and something from this land enters me, quietly, gently. I want to reciprocate, to enter it, but that is harder. The giant petrel loops around the stern, a thin brown curve, a jot with eyes, wingtips skimming millimeters from the water. Spindly trees, all elbows and noses, on the horizon of the green sea cliffs. New Zealand and Scotland, yes, but cleaner—more silent—more vast—less seen—more integral. Dolphins play under the waves—a certain fact—chattering and swapping songs and teaching the children. It is a fine day for living here.

So, now that the circle has turned so that I am here, I have my messages to deliver, I have ears to listen. The next step: how do we begin? With the small talk of your “natural history?” Perhaps, in moderation, but it is only small talk, and one way at that.

Patience. Let you come to me—I am here, watching, waiting, eager. The language barrier exists, but I have learned enough even by being with humans to know the superfluity of words, however convenient they at times can be. Standing on the bow, a few instructions come. Drop words. Forget words. Music—well, that’s in the right direction; it’s warm, but not hot. Eyes—same thing. A veil is in front of my eyes, a carefully constructed pattern dutifully offered by my brain. Something is behind it. Already I am seeing glimpses. Ears—nose—skin—taste—all a little better, because the brain is more clumsy, less well-trained. Skin possibly best of all. But it is the intuitive senses, the tools of the other-world, that are the only hope for communication… and here I am a baby stumbling about, making discoveries, having no real idea what I am doing or words to call it—something vague I have kept from others about “opening the heart,” something about “centering,” about “listening to the still small voice of God,” about “living in the present.” No concrete help on how to talk with dolphins or petrels or shaggy cliffs of beech trees, or how to listen, either. Trial and error, concentration, dropping words, patience. Silence. Maybe a bit of music. And coming to you, alone and ready—to hear the silence, and then what moves behind and beyond. To see the beauty, and what beauty protects us from seeing.

Already, a few things have come, which I’ve managed to translate into words: the Goddess has brought me here for a reason, and if I am open to doing her work—as I am—the work will be done.

Perhaps another instruction: listen to dreams, and to our myths. We do not mind if you try to translate them, even if you bungle a few things here and there.

Feb. 14

Yesterday—a woozy, already dreamy day… weathering diarrhea, acquiring sea legs, getting by. No matter how you look at it, the voyage is long. Cape Horn, in the morning, was dreamy, unconnected—a place to spend two hours, better a place to spend two weeks or two months. One of those learning places, potentially, like Minsmere, like Robson Glacier. For two hours—a millisecond—our ship emptied dozens of scurrying bright-red creature who quickly scattered themselves over the new hills—startled some penguins—left footprints in the mud—dropped a few pieces of tissue paper—took their photos, exclaimed their exclamations, and left. For the most part, I too wandered, a bit dazed. All I clearly remember is that the hills were screaming. Here, on the very tip of the continent, a thousand brays rose and fell, hundreds of worshippers chanting something to the sea and sky. Pleading? The biologists can talk all they wish about those calls being directed to one another, to being functions of territory or some other drab idea. Maybe, on the planet level, that’s true. But I swear that chorus was raised to the sea and sky. An invocation, a pleading, a vigil, on behalf of everyone. It is good to know that on the tip of the continent, a thousand penguins are interceding on the planet’s behalf, raising their voices, day after day.

That, and being bewildered for a few moments in shoulder-high poa grass, the penguins shrieking in alarm as I stood and spoke, helplessly, in English, “I mean no harm. I come with honor and respect.” But it would take weeks—months—years—to move past this language barrier. A secret world beneath the poa grasses, sunlight filtering through flowering boxwoods, sheltered and windless. The Chilean guys thrust a puppy in my hands and looked crestfallen when I said, with regrets, that I must go, the boats were waiting. Inside their tiny chapel, Mary and her divine child wobbled on their wooden pedestal from the force of the wind outside. A clean, hard, lonely, magnificent place, that I will likely never see again. The dogs barked desolately on the beach as the last Zodiac pulled away.

Cape Horn

Earlier, the previous day, we rode to the foot of the Romanche glacier, certainly one of the most sensational in the world. A waterfall the size of an eight-lane highway—at least—covered the granite below the glacier. I took no photos. Tears began in my eyes as again a certainty came over me that the Goddess was granting me this sight for an obscure yet important reason. Rainforest and glacier in spectacular juxtaposition—steamer ducks absurdly half-flying across the water. Do the steamer ducks croon to their eggs the old myths about the days when they could still fly? Do a few young steamer ducks determine that they will be the ones to re-remember?

A few more words about culture. There is, in fact, an under-40 crowd, not a large one, but we keep finding one another…for example, in the gym, or on the bridge or at meals. Jennifer and Tom are engaged, Montana outdoors-people. She writes poetry and did environmental studies, he plans to half-own a bike shop after years of rangering in Yellowstone. Jerry is a fairly well-established, New York-based wildlife photographer with an earring and somewhat wacky sense of humor. Ronald is a famous Dutch alpinist, a happy-go-lucky guy with a certain endearing tactlessness and what I am tempted to call superficiality, though that sounds too judgmental. David B. is a geologist, once with OSU, with a lot of McMurdo experience, humble and friendly. Keith is one of the staff’s husbands, along for the ride, who likes talking global issues with me, but who is in a pre-empowerment phase. Manny, whom I seldom see, is so much the stereotypical New York corporate lawyer handling merger and transfers as to make the stereotype delightful in its full bodied-ness! There are others, too, with youngish spirits, but that gives an idea. My favorite times have been on the bridge, late at night, where I have made friends with Nestor, one of the Filipino navigation officers. Hanging out with the crew and the staff is restful and centering. But I enjoy the challenge of the older folks, too, and I think I’m good for them. I do a lot of briefings at dinner on Antarctic politics. There seem to be a lot of misconceptions about environmental groups’ positions on tourism. Tony, the expedition leader, seems to believe that Greenpeace opposes all tourism. Perhaps I should find out about putting up a flyer on the bulletin board, after all. Now—calm seas—the middle of the Drake Passage. No land in any direction. I have blessedly found sea legs, for the first time in my life, and almost enjoy the boat’s graceful rolls and plunges to the rhythm of the ocean. Yesterday I saw a humpback, becoming the first person to spot a whale. So, watching is rewarded in the first five minutes; then an hour goes by and there are only whitecaps and swells. …Again and again, you recall that flash of vision, the sleek dark body and knobby fin curving through the water, until you yourself begin to doubt whether it was not only a hallucination. You try to grab on to certainty, but the waves and sky and light are slippery. You start to wonder whether it even matters or not if it was an illusion or “real”—whether a “sighting” is anything more than your own dream in the water.

So, everything happens and nothing happens—the voyage leaves behind the spectacular desolate peak of the Horn in the mist, and we skim the surface, with lots of opportunities to dive deeper if we wish, but it is not a choice for the timid or unprepared, or even for those who are simply unwilling.

Afternoon

Anticipation is key. You sit on the bow, and learn to hang on to your notebook; you stand, and learn to love the swell under your feet, to feel in it something soothing, even reassuring. And there, to the eye and the mind, there is nothing whatsoever: a horizon of deep blue water maybe five miles in all directions, and the sky. Maybe a couple of petrels, a prion, an albatross. But none of the things to which you are accustomed to seeing under the glance of heaven. No ships, or land, or smog; no landmarks or seamarks at all, save the sun. The voyage is long, but that is part of the destination. You do not sail this course casually, on a whim. You do not point your craft at the limitless horizon, hour after hour, without purpose. Oh, there may be a few dolphins on the way, but you cannot expect companionship, only be grateful if it occurs. This is, of course, not the same as sailing alone. There is a small world of experience aboard, of languages and lore and know-how. The captain and crew know exactly what they are doing. The cruise director flawlessly executes a well-timed schedule. Computers hum, engines moan, radar spins, all for the sole and single purpose of carrying you to this place. It is touching, and rather embarrassing. What did you do, to happen on such a voyage—what is it really that is bringing you here? And what are you supposed to bring home? The ship has no answers, nor the open sea, the means of waiting, the distance that prepares you. All you know is that you are traveling to a strange land, and once the ship has arrived, no one will give you any guidance as to what to do.

Although instructions begin to trickle in again. Take off your shoes and socks. Play tunes. Limit photography to a few times and places. Escape the temptation of schedule. Thanks to it, almost no time is empty and vacuous? Almost nothing genuine has time to whisper, “Psst! Hey you!” And so it goes, through the years.

You get used to conditions—you do gain your sea legs and accept that the world is not stable, with surprising alacrity. But it is so easy to become enamored with logistics. How to lash the chairs to the deck. How to take a shower when the floor heaves like a merry-go-round. Worst of all is the temptation to follow a schedule. We work so hard to keep ingesting things to do, to ward off the terror of wild, pure, fierce free time. You want to go on a peerless voyage to a holy land and instead, the bell rings and calls you to tomorrow’s briefing, to tonight’s dinner, to a party hinged to a date hinged to a calendar that means nothing here. But there is something bumbling and dear about these packaged cocktail parties and teatimes…something that you don’t want to coldly toss overboard, despite their difficulties—only tame and restrain whenever possible.

You learn anticipation. And quickly you learn the randomness of grace. You cannot look for whales, for dolphins, in the wide rolling sea; they either come to you or stay within their world. How thin our possibilities for overlap. If I were to fall into their world, I would die within minutes; if they were to fall into mine, they would last only a little longer. We might as well be from different planets, allowed to visit only in well-insulated and self-contained spacesuits. Yet they must reach for a bit of our air, and we must drink some of their element to live, as well. The membrane is broken by our keel, and by their sleek huge bodies bursting through the skin. We see their spouts, they hear our rumble. We touch and yet not touch, always, and never.

Sitting on the deck, doing what one cannot do—look for whales—all kinds of preconceptions dissolve under the relentless emptiness of five miles of water. You find yourself believing that one side of the boat must be better than the other, for instance, and then the rational mind steps in with arguments and reasons for why, statistically, one side is quite like the other. Yet the idea persists, through several rounds of persuasion, and several times you almost move your chair. You refrain, however, remembering that this is silly, that the receiving of grace cannot be schemed or your chances enhanced by cunning; that you will simply sit, and look, and be humbled by the odds and the vastness.

Then when it does come—the blow! The slow yet instantaneous rolling of the huge body, the excited shouts from the marine mammalogist of “finback!” There is no way to remember the binoculars, or anything else: the knowledge is instantaneous, indubitable and then, as quickly, open to doubt, as the mind struggles to remember what the body has already received like a benediction and stored in its deep recesses. Later, the memory is like a postcard or a movie: flat, unlocatable, destroyable. But the receiving itself remains and draws you to the upper bridge, again and again.

At 11 o’clock, Nestor, my Filipino officer friend, and I adjust the ship’s lights for icebergs. We are 90 miles from Deception Island, from the Antarctic. We are, for a moment, at 63 degrees—63 degrees! Darkness falls, penguins fly from us like so many sandfleas, and the long preparation is nearly over. Often in the last few days, I have been thinking much of Annie Dillard, carrying on a dialogue with her, undoubtedly mimicking her, even. But in some key places we diverge. I cannot write, as she can, that the will to see and to communicate is wholly one-way; that only silence lies beyond those barriers, that God in fact “doesn’t give a hoot” about our efforts to reach him or her. The stars do care, if we walk outside to look at them; the penguins do have some feelings about the matter; God does give a hoot. The other way makes for good writing stripped clean of sentimentality, yet stripped clean of something else, as well. I know this not because stars, or penguins, or God have told me these things; no, I am merely hearing echoes of my own desires. It is knowledge based on not one shred of evidence, not one jot of data, nothing at all but intuition, and the knowledge that comes not through searching, but through grace, a sudden blowhole, an indisputable glimpse of body.

Feb. 15

Then you awake, and it is morning, and you are still blinking from sleep when you are efficiently hauled ashore and deposited in the other world. Somehow, the slides and stories did not prepare you for the reality of 300,000 penguins. A moist film of penguins covers the hills. The film shivers, undulates, and—this is the most disconcerting – it sings. Loudly. Up close, a few number of penguins can be said to squawk. But squawk is not the word for penguin song en masse. I looked up, half-believing, when several times I thought for a moment I heard music. I mean what we normally term music, that is; notes, melody, the echoes of a hymn fading in cathedral stone. Music? It would fade, my attention would wander to a single squab’s croak, I would move on.

A chinstrap penguin colony

So, I was incapable of concentrating on individuals. I was aware only of mass, of enormity. I thought of starlings, and wondered if this was not penguin-ness gone amuck: stamping the hillsides into muck, littering the gullies with bloody, picked-clean carcasses. It was like a view of L.A. from a plane or cicadas in a wheat field. If I had not already known of the whales, and the corresponding penguin bloom, I might have simply marveled. But I did and I did not.

I did find one chick, quiet, phlegmatic, completely self-contained and unself-conscious, who regarded my strange appearance with such serenity that I was able to single her out for a few moments. She stands, and waits for the last of her down to shed, for her time to go to sea. Would that I could greet a stranger from another world with such inner peace, and, almost, welcome.

A chinstrap penguin chick

We lost an able-bodied seaman in the surf, who was trying to haul in the last boat, as we stood silent taking photo after photo of a painfully beautiful beach filled with rafts of penguins sortie-ing into the waves, and fur seals croaking in their midst. Beyond, in the mist, rose icebound mountains—the continent? There was no time to see it. The last boat should have left 10 minutes before. I crammed it onto film like a person sure it could be hours or days until the next meal crams bread into her pockets. How persistently the word “paradise” pushes into the mind, despite the stink and bloody skeletons and the brooding, watchful skuas, and the red-toothed jaws of the fur seals.

Antarctic fur seals

Later

Landing number two—littered with history. Vaguely Vedic faces painted on rusty whale oil tanks, staring out to sea, and blazing candles. What did that artist see? Fur seals talking, galumphing, twitching in their dreams and opening one eye at the sound of a camera shutter. A huge slice of blue whale cranium, the spinal cord hole surprisingly small (only the circumference of a grapefruit), a scattering of lichen on its surface. Great miniature moss-lichen forests. A sea-cliff deep and black and green and beautiful enough for lingering for days instead of minutes.

I would not mind our cheerful herd at all if they would not speak. If they did not insist on small-talk just at the one moment that it might be possible to stare down a fur seal. If they did not discuss trekking in Nepal while their boots are buried in still warm pumice. But on the whole, it is easy to forgive our bumbling, brainless cheerfulness. On the third landing, we walked to the edge of the crater like so many intergalactic tourists dropped off at the wrong planet. What is there to see here, anyway? It doesn’t take most very long to tire of mist, rain, rock, cinder, ice, mud, water. But I loved it. I climbed on high as I wished, lay on my back, felt caressed and kissed the light rain that soon began wetting my face. I felt the heat and the deep, deep swells of hot earth beneath me, and felt my own heartbeat and was happy.

Later, on an afterthought of a beach walk, I saw a black-necked swan, which caused a sensation on board and sent the birdman and expedition leader in hot pursuit. I gave thanks once more that I did not choose the path of science. It will go into record books, but thank heavens I do not have to bother to put it there.

Midnight That Night

We have crossed a boundary. Again and again, I run up the four flights of stairs to the upper deck, joyfully, with the light steps of a lover. Standing under the still-illuminated sky, the clouds silhouetted in the same fathomless color of the sea, the silent majesties of icebergs and icebergs slipping to port and starboard, Orion unexpectedly hovering low, and unfamiliar stars opening the east, where the cloud-shrouded, glacier-bound continent glimmers… Sleep is an effort. I want to stand there without time, without end, loving the purpose and harmony in the movement of our ship through the night. Downstairs, in the warmly lit chartroom, I gaze raptly at charts and bend over dials all the more magical in their mystery. There are friends there, fellow human beings, who are warm and friendly and fun to be with – I would really miss humans, with all their failings, if they were to disappear, to leave us… Upstairs, I begin to know, deeply and without words, why some can never leave the life of the sea, why some would choose to give up all else for this: the clarity of night, the grace of purpose, the satisfaction of setting a course, the purity of stars over water, the silence, the round full wholeness of our oceaned earth.

This evening grace came again to us incarnate, in the form of a right whale – surely the oddest, most majestic, most beautiful creature I have ever seen. It took dozens of minutes to sort out the odd jumble that turned out to be its head: the jet-black baleen, the ridiculously pleated jaw, the double blowhole and double-hammered snout. It lolled, fed, turned flippers, fed some more, blew, held its bizarre body arched in the surf as water sieved through its inconceivable mouth. For 30 minutes we watched it while our whale man jumped and chattered to keep warm, unable to tear himself away. Someone spotted it, casually, after dinner, above the bridge. “Who has binoculars?” I saw something huge and purposeful riding through the waters. “Mark!” I yelled. “Someone get Mark! This thing looks pretty weird!” When Mark came and said, “Right!” I dove below for the binos. The ship pulled around. The passengers emptied on to the decks.

No one can earn 30 minutes with a right whale. No one could possibly deserve it. It is a sheer gift, given for joy, unconditionally, out of love. You stand and look and cannot believe you are receiving such a miracle, that it is personally and presently happening to you. You think of the visions of angels you have read about, and you realize that those, too, were unearned, that giving is the very nature of grace; that no one is too petty or too limited not to be showered with this undeserved love.

You receive, and you retain enough mind to think: This is it. This is my chance. She is there, three of her body lengths away. You can hear her breathing. You can hear the water cascade through her jaws, and see the ungulous leisure of her raising of flukes. You think, and scramble for intention, for a message; you flounder as you try, in this state, to coolly compose a thought out of words. “We are here,” emerges from the jumble, and falls away; you scramble again. Later, you think of eloquent and meaningful word packages to telepathize across the waves: “We come to you with love and honor. Hear our greeting. Please have hope. Not all of us are destroyers. We are working away. We are trying. If you would like to tell us something, please do.” But at the time no words can stay long enough in the mind to form sentences. All words are crowded out by a deep, deep, joy. You are here; she is there; you are both alive; you are wonderful together. You can think only of the blessing itself, not of putting it to some use, however worthy. You could watch the whale all night. But it is too dark for photos. Most have gone inside. Even the frozen, chattering marine mammologist has withdrawn. Twin blowholes catch a faint glow from the sky. In the silence, it sounds like good-bye. The engines rev, and you stare at the receding patch of water, too moved to speak, too full of your gift to take it inside, and go on, for another hour. The bergs capture alpenglow and the stars take the watch before you can manage to leave.

Feb. 16

Then the time comes when you become greedy. You have received and received and received; you become a junkie for these gifts. You expect too much. The light isn’t right. The sun is obscured in cloud. The seals don’t look the right way, there are red padded arms between your lens and the minke whale, you fret over the gas sullying the crystalline waters, and the noise, and the small talk. How quickly we turn a gift freely given into an expectation! How demanding our receiving can be! And so it is not enough for God to show his face once; we absorb that gladly, then are disappointed when tomorrow he does not come again.

And, sadly, some of us turn bored. It must endlessly frustrate the givers, how short our patience and attention is for receiving. How so many venture so far and then, incredibly, turn back, and even more incredibly, not even realize there was more to go. We are addicted to novelty. “Did you see any new penguins?” the couple at dinner who did not make the last landing anxiously inquired, and were reassured when we said no, only the same penguins we first spent an hour with this morning, of which many already are apparently tired. The hunt for the perfect photo sustains many. But the hard fact is that penguins, in truth, do not do very much on land. They stand. They waddle. They arch their flippers and hop from one mucky rock to another. Sometimes they beat their wings, point their necks skyward, and bray. All these brays are, as far as I can tell, monologues. No one makes any attempt to comment, answer, rebut. Once, perhaps coincidentally, two adults brayed at exactly the same moment, facing one another. Then a third adult joined in, and finally a chick, who then found itself braying alone in a half-adult-croak, half-chick-peep, exactly like an adolescent in the middle of a voice change who had missed the choir director’s signal. One chick, flat on its belly for the first 10 minutes, then picked itself up, shook itself down, squirted some guano, yawned, and looked around, blinking. The chicks do not seem to know what to do with their suddenly huge bodies. They walk gingerly, doubtfully, as if every move could bring some unwelcome surprise. Mostly, they do not try walking at all, but stand, or lie flat like little boneless heaps of fuzz, beak, and feet. The adults, too, seem perplexed at the instant hugeness of their offspring. They often gaze at them with, perhaps, an air of mixed pride and trepidation. Perhaps they are wondering whether, if they keep feeding them, the chicks will keep swelling and swelling—at this rate, in another month they will be seal-size.

But the penguins are not bored. Boring, perhaps, to the people roaming the muck, who quickly discover that the penguins on this side of the island are very like those on the other side of the island, that there is no point stopping for penguins, that they are all equally fat and dirty, streamlined and immaculate, waddly and tippy as bowling pins. The people wander and driving snow in a 40-knot wind hits their faces and they head back to the ship. And the penguins stand and sing penguin-song and dream penguin-dreams. The mountains nestle under cloud, the wind pushes, the ground is littered with old feathers and the pale pink carcasses of krill. The penguins dream, perhaps, of their wonderful new feathers, so tight and warm and waterproof; they dream of clouds of shining pale rose krill, of leaping through the waves far out to sea, of speed and the joy of water-flight, of lying on their backs during the long silent winter and letting the currents take them, enwrapped in their own warmth, content with their companions, while the ice clatters and the whale-songs murmur and drone far below, and then they dream of the summer, of the awkward lessons and responsibilities of creation, with all its exhaustion and discomfort and satisfaction. Penguin dreams. Penguin blessings: may your oil be bountiful, your feathers warm, your beak accurate, your flippers strong, your feet sure; may you go far from shore in contentment, and return to land with gratitude; may you swim together for all time. May you fledge fat and healthy chicks; may you teach them all our songs and stories, as you sway together on rock and ice, in water and wind. May your passage between the bills of the skuas and the jaws of leopard seals be long and full; may you learn to give-away to them when your time comes.

So, it was all a misunderstanding, no doubt, those first few moments on Bailey Head, but a very wonderful one, when the penguins disarmingly waddled directly toward us. “Friendly little buggers,” said one man, astonished. It was, of course, only because they were headed to water, and we stood in their path. But after so many years of the pain of knowing that all things fear and flee from our very presence, and rightfully so, a pain we are so used to as to usually forget, it is one thing when a wild creature does not flee. It is something totally else to have them walk straight for your feet, flippers wide and embracing, as innocent of your crimes as human children.

But despite the gnawing of greediness, and the blizzard which set in at midday, it was a full day, replete with marvels. It took me an hour-and-a-half to find the penguin family I wanted to find, huddled on the slope of the continent, and then I had only 10 minutes with them. But at least we had a few moments alone, and I sang to them, and a few of them listened. The continent felt different—massive—with only a thin outer skin of life as we know it. I snatched five rocks hurriedly—too many things, too much hurry—and will look at them later. The penguins were gentoo, quite phlegmatic, but still feeding their chicks in lovely bill-caressing demands and givings. For a few minutes, a sun almost appeared and the water came alive. At first, I could not relate to the Zodiac tour: the Disneyland ease, the sound of the motor, the constant streams of words, and all these red bodies. But the seals saved us, resting and playing on their floes. Face to face with a brontosaurian leopard seal head, I had to admit there was no other way to approach, much less enter, these creatures’ world. I also loved the minke whales, their fins slipping among the fields of ice with such grace. It was, of course, impossible to try to enter any of these creature’s herds on a big noisy black raft. It was only visual. But the visuals, I confess, were hot: still water reflections, ghostly seals under the boat, fuzzy shag chicks, arctic terns, Caribbean blue icebergs and pellucid waters. At breakfast, also, two minkes, traveling fast. So, complaining is not possible.

Gentoo penguins, adult and chick

The blizzard continues outside unabated. Time has no meaning for it. It will quit in a few hours or a week. We can only wake up and greet whatever morning we have.

So, you stand at the bow, where the wind is strongest, the spray highest, the chances of seeing the greatest. You stand, the ship moves, the clock stops. Your eyes fill with tears from the wind. Your eyes are scraped raw and hurt at night, before bed. You know you are just beginning to see, and the bridge calls you, despite the snow, despite the close-hugging cloud and rain. You want to move again. Up with the anchor! But the lights in the bridge are too bright, and your friend is putting charts in order. You do not go inside, tonight. You will wait for the ship to sail, for that illimitable, exhilarating sensation that there is nowhere on our water planet you cannot go, there are no borders or fences to stop you: your ship is pure freedom, pure purpose, and can sail any dream.

Feb. 17

In the morning, doubt. The face is hidden behind a veil of cloud reaching almost to the water. You weep for the cliffs you will never see and wonder why are you invisible, today? Why cannot I look at you? You half decipher the Argentine satellite map and know it could be this way for a week. Mistrust, and a touch of self-pity, but you avoid most of that, thinking: change will come. And blessings can’t be collected like potatoes. More is not necessarily more.

Rocky island and icebergs in the harbor

An hour later, all doubt has also lifted and is forgotten. The ice hills are streaked with penguins, and a dozen huge bergs loll on the other side of the island. Your photography becomes methodical, rhythmic, intent as you switch lenses and cameras. You even, God help you, allow yourself to agree when someone offers to take a picture of you and your mother in front of penguins. The Adelies are the wind-up dolls of the penguin world, sleek and manicured, their white eye-rings giving them a look of perpetual astonishment. Over the island, beyond the last castled berg, there are hints of a band of blue sky. The sky? You had forgotten about the sky, and now it is opening, unbidden, in yet another blessing.

“The light!” Photographer Jerry shouted halfway through our zodiac cruise, in one of his few utterly serious moments. And indeed the light, when it came, came slowly and with dignity: first illuminating a few bergs far to sea, then creeping steadily nearer the minke then suddenly striking the mountain, the ice, the spinning leopard seal, in a great single chord. We leaped up, exclaimed, laughed, snapped photo after photo, like children released from school; the holiday had come. The leopard seal circled and spun, rose and played the minke or perhaps she believed she was defending her very life and way of life, the way she swirled under the boat time after time with teeth bared and jaws wide. Playing, we all said, but no one would have put fingers in the water on a dare. The ice floe hollowed and turquoise, the cleanness and purity of her wild fierce face, the power of her breathtaking swoops and loops and hoop-de-hoops…

Leopard seal

Looking back to catch the light, I saw two Adelies leap bolt upright out of the water onto a floe. It was not hard to see why. The leopard seal prowled the edge of the berg, eyeing the penguins and harumphing intention, while the Adelies, eyeing it, scooted nervously a few steps higher. Later, we heard, the seal caught one of these penguins, or perhaps another and devoured it, chunk by chunk, in front of another boatload. But we were off again, seeking light, and finding it: blue grottos, carved ice towers heaped in front of mountains, penguins sprinkled like chocolate shavings on ice cream. One Adelie group nearly treated us to a mass dive, but thought better of it, and turned their fat black backs to us. Cowards! We called after them.

A day, so far, for visuals: almost no rock under our feet—but the light! The mountains finally and splendidly revealed! The sun caught and shattered in the waves! A deck chair, the beginnings of sunburn, and half-a-horizon of ice-bound mountains dropping into the sea. The continent is so different in character from the islands. You could imagine living on the islands for a week, or half-a-year. Lots of life lives on the islands – they are steeped in dung and feathers and bodies and familiar, fetid smells. The continent, on the other hand, is a giant painted backdrop, not inhospitable, but rather, untouchable. Unable to be touched. Unapproachable on all sides, but there is only one side: the one facing you. It is as lifeless a place as one might hope, or not hope, to see on this planet, yet it is not dead. Something quite else—it’s hard to say— but definitely not dead.

Feb. 18

On the navigation chart:

“The prudent mariner will not rely solely on any single aid to navigation, especially on floating aids.” A wonderful, cryptic sentence, dense as a rune.

You see a whale off the bow—you know you have seen it—it slips to port and gives only one more glimpse, which no one else sees. The ship glides on without hesitation. You know you have seen this whale. But at other times, you wonder if you are seeing only your own desire in the waves, your own reflection in the water. Such is the nature of a miracle revealed singly in the multitudes, seen only by one, while the ship glides.

You have been voyaging, it seems all your life. You can hardly remember your landbound life. The ship, initially so cramped and contained, has become the world. You reflect that every story you have read worth reading was some sort of voyage. And that voyages have beginnings, middles, and—sometimes—ends.

Last night, you encountered a government bureaucrat, and the hair rose on your neck. You turned part of the briefing into a press conference. “You’re a journalist, aren’t you?” one observant person said today at tea. Staring at the floodlit tanker and the rusting, sluggy heap rolled belly-up on the rocks a half-mile from the penguin colony, it was hard not to sigh and accept that, no doubt, this is one reason Gaia had brought you here. The conversation, afterward, in the lounge, depressed you with its pessimistic tone. The difference between caring and action, knowing and empowerment, flattens you at times. Some people here see me as a fighter. But I don’t feel I am fighting. It is not a question of fight, but rather—how much do we love this planet? How much do we love its living things? And—this is the key— how much do we love ourselves and our own species? How much are we willing to nurture and believe in people, and to love them, and to think they are capable of caring? In the intelligent, concerned, thirtyish-people here, there are definite strains of hatred, or at least disgust, with our own people. “People don’t care as long as they can watch Wheel of Fortune every night.” That sort of comment. I tend to turn earnest, then just be silent, feeling that the process of empowerment cannot, after all, be told. I tell some stories, hoping for the best. Perhaps I could do more, but I am not sure. (Editor’s note: The Argentine ship, Bahia Paraiso, had recently run aground near USA’s Palmer Station, spilling more than 200,000 gallons of diesel and airplane fuel over a 40-square-mile area, with devastating effects on wildlife.)

So, there is an expose here, probably, and someone will probably be interested—and yes, I have too much to do already—but what’s a couple of workdays, a bit of frustration with editors?

Resting in the sunshine on the deck near Faraday, a sudden message came in from the penguins. “Make love,” they said. Later, when the humpbacks rolled and waved and lounged near the bow, in utterly no hurry to do anything at all, I thought I picked up something else, through the static: “Remember joy.” Still later, the half-dozen minkes leaping and breeching in the shadow of huge bergs were even more direct. “Play!” they said. “Play!”

“Why do they do that?” the travel director asked the whaleman.

“I think what we saw today was mainly social behavior,” the whaleman began.

“They were playing,” I translated from the wings.

“Right. They were playing,” the whaleman said and went on.

What I saw was a pod of beautiful sleek thirty-foot whales swimming at top speed through the ice-floes, surfing and porpoising in something that was not quite synchrony, and not quite randomness. Then one gave a little leap in the air, out of pure high spirits, it seemed. And the others caught on, laughing with their huge beautiful bodies, shooting cleanly from the water nearly to their tail flukes, twisting to fall flat on their backs, and, I swear, trying to make the biggest splash they could. “Play!” they laughed, as our boat glided farther and farther, “Play!” But we were dead serious in our solemn cruise into the bay, turning about, and cruising back. We did not see them again.

Tonight, Nestor tells me that “floating aids” are things like buoys, and they are generally untrustable. They move. As a cadet, he ran aground when his captain followed a wayward buoy near Norway. The British Channel charts are corrected daily.

I never tire of the charts. It is important to know the soundings if you are going to set a course. The blank spots give me a new understanding of the term, “uncharted territory.” Even this ship takes soundings, at times, as it goes. The sea must be felt when it cannot be seen. The sonar waves bounce, the line reels out on the spool and stops. The pencil comes out and makes a neat little cross. Gingerly we weave through the narrow channels, feeling and yet, of course, avoiding touch. Canyons, pinnacles, mountains, valleys glide below, that the whales know well, and even the Weddell seals have explored. Our topography must be equally mysterious to them. What can a land mountain mean to a minke beyond a murky glimpse, a theoretical landscape? We glide over waters too deep for the echo-machine; it blinks red numbers and Nestor turns it off.

“We will miss your company,” says Humberto, the radio officer. “Maybe someone else will come on board who will like to come to the bridge,” I said. “But they will not be you,” he answered. It is a lovely thing, to be liked. We have a good time together. The Filipinos are so much warmer than the Germans, although they are also nice. But they seem to communicate and work together well—all in English.

So, I have lain on rock, sung to whales, greeted seals, hailed many icebergs, and petted a penguin. At this point, I can say I have been here. The rest is gravy.

I have also frozen my fingers, smeared guano over my pants, broken my telephoto, shot more film than I brought, eaten too much, sat alone on the bow staring into the wind, prowled the bridge like a person hungry for the helm, the charts, the compass. I have dung and rock embedded in my boots, perhaps perpetually. I haven’t had time to take a shower for three days. I will miss this ship.

Feb. 19

Too much wine, too little sleep: so only code words.

Brash ice. Grease ice. Dividers. Hard to starboard. Port five. Shuddering against a floe. The sea, in dead calm, freezes. Less than one percent of the Adelies have not left for sea. Tabular bergs beyond belief. A green crater lake. Wet snow. Snow-cone-blue bergs deep aground in the water. A cape pigeon chick spitting, rightfully so. Minkes in the morning, for joy. Every day’s mood so distinct. Many hours on the bridge. Are we really heading back? Penguins darting underwater, quick as guppies.

Icebergs

But after all this, how can we possibly resent a little snow, a little fog? Miracles are our daily fare. We are fully in the rhythm of shipboard life. Going back will be hard. Haven’t we sailed together for years? Hasn’t this always been our life: to wake and concentrate each moment on beauty, on receiving and giving love, on the voyage itself? So—an inevitable, temporary phase—we even become calm about penguins. But whales—never. Whales are still and always the quick bolt of grace.

Feb. 21

The Drake Passage is like a birth canal, the physical and tangible barrier separating here and there—going to Antarctica would mean far less without this anticipation, and this denouement.

Atmospherics, tonight, and in the last few days. Tonight, swells have relaxed into calm, and we mosey along at six knots while a just-past-full moon lights half the sea and Nestor, at last, successfully points out the Southern Cross to me. A calm, magic night, with anticipation, hovering in the air, and the poignancy of endings. We have had our small world on this ship, and it has in most ways been a good one. I don’t feel I will see many, or any, of these people again, but I will remember a few of them for a long time.

So you voyage, and you find what you seek: you stroke the soft plump body of a drowsy penguin chick, and tell it your message, and tell it to someday sing to its children the story of the strange dream it once had: of a time when a human came softly and slowly, and spoke in whispers, and said to have hope, and that not all of them were destroyers, and that some were doing all they could, and that they had come to us with love and respect. A strange, wonderful dream that I had when I was still a chick not fully fledged, just before going to sea.

Gale befriending a gentoo penguin chick. Photo by Yvette Cardozo

This chick was more fearless than the others, and soon my attention focused on it. I am attracted by fearlessness, I guess, and the willingness to risk trust, in both people and penguins.

The last two days seemed to go very fast. I could have spent all day at Cuverville Island as the sun illuminated the water and ice with deep and interesting blues, whites, silvers… “Sunshine on my penguins makes me happy…” though again, only marred by how brief it was, how minutes after the sun came out we had to go, go, go. I climbed a hill and was dive-bombed, with fierce dark intent, by a couple of pairs of skuas. Okay, okay. I’m getting going. Just one more shot with the polarizer? No? Okay. We played with two humpbacks and watched minkes jump in the distance, but the clouds moved in at Charlotte Bay, and we never saw sunshine again. Whalebones, Weddells, and the trusting chick at Trinity Island. Then a long cruise toward the Antarctic sound. More tabular bergs than imaginable. A minke breeching 150 yards off the port side. Is there an opening? Yes. Bergs and bergs… but Paulet a small disappointment, as wet snow fell hard, and only one percent of the Adelies remained. Shags are technically as beautiful, but somehow do not have the same appeal. Beautiful ice strewn on the shore. A treacherous climb to the nests of cape petrels. It turned out to be our last landing. A “freak gale” wind blew gusts to 55 knots the next morning. For the first time, a landing was canceled. We had to stand and try to soak up our last moments in Antarctica only with the eyes. A few dark shapes slipping into the mist. A few last icebergs, heading north. A sense of incompletion, but a haunting, perhaps not an inappropriate one. The storm was also part of this land. It is not always so easy. Don’t take anything for granted. Even with the best of planning and equipment, luck is still essential, nothing is guaranteed.

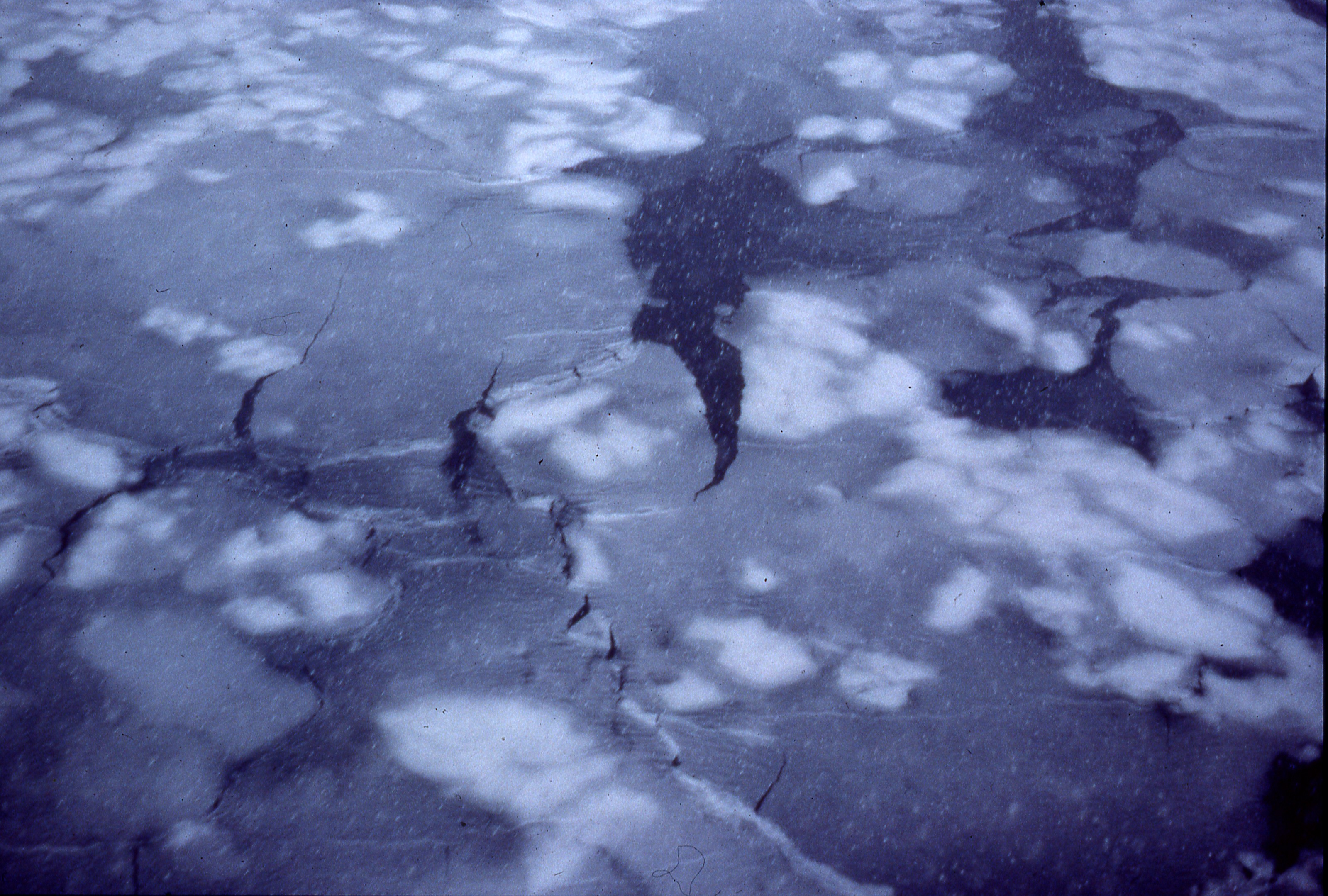

In an odd way, one of the most special sights for me was the grease ice forming in the blizzard on the way back through the Antarctic Sound. Does it have something to do with the snow? I asked the captain. “No, the sea is freezing because of the dead calm. Because we are in Antarctica, and winter is coming.” The patterns, fractures, jigsaws, cracks and holes were infinitely varied, different, fleeting. I leaned over the bow and shot again and again. The sea was speaking. “Go.”

Grease ice

It is hard to believe, in what varied forms earth and water can come—how one can look again and again at landscapes of rock, ice, cloud, sea, sky and light, and find each one different, each one unexpectedly beautiful.

Feb. 22

Quite literally we drowse and doze through our return, and, waking, set foot on land and look around blinking in the sunshine. Where are we? What planet is this? Could it really be the one we just left? Small pieces of memory surface from the passage: you remember being served orange noodles and a roundish thing covered with green and yellow sauces; you remember making a speech, you remember the hourglass dolphins in the stern wake, some good talks with people, standing on the top deck bow in the sunshine, glorifying. Puerto Williams, not at the end of the world in the least, is so familiar as to feel like home. You know beech trees, lichen, heather, ducks, geese, caracaras, lapwings— you’ve seen all that before the journey. The day is pleasant as you find your land legs and remember green. There are mountains, children, dogs, woodpiles. In the museum, you find confirmation: “According to Yamana legend women once ruled the tribe. But the men decided to kill all the women except the younger ones, thus taking control of the community. This event is remembered in a ceremony ‘Kina’.” So… not at the end of the world, at all—right in the mainstream, I’d say.

Lots of good-byes, a long journey home. Dave teases me about wanting to stowaway on the ship. And indeed, it is hard to walk away from the little red ship so fleetingly tied to port, so quickly headed in return. Wake-up! Now land muzak is playing and a Chilean stewardess is handing you a rather tasty chocolate goody. Okay… I will eat and look out the window and be happy. The ship will sail toward the dark tunnel of the passage, without me. I hope someone curious and smiling goes up to keep Nestor company, as the stars come out again and Cape Horn looms on the orange screen and the radar sweeps squeak and the giant petrels swoop through the swath of moonlight.

I wonder what name the shags have in penguin language? Possibly something that would translate, “Those-Who-Swim-Through-The-Sky.”

In the night between the sound and Nelson Island, I left Nestor about 11:30 p.m., with the wind picking up and a double watch out for icebergs. In the middle of the night, I half-awoke to the scraping, beating sounds of ice against the hull, and rough seas; our ship felt small and tossed and fragile, but what is there to do, but close your eyes and go back to sleep? When the sea awakes?

I could not have dreamed I could suffer the loss of a telephoto lens on day two-and-a-half with so little pain. It might have been the best thing that ever happened to my photography. To get close to penguins, or seals, I needed to get close. I explored the possibilities of a normal lens. I shot more black-and-white and thought more and worried less. Photography was, of course, a mixed blessing, but altogether worth the distraction, I think. I do insist I can bring some piece of this home. I will not relinquish it all. Twenty-two rolls of film, some whale bones—Sh! Don’t tell customs!—five rocks, a handful of addresses, one stuffed penguin, one tacky plastic penguin, some permanent alterations to the way some of my clothes smell. Light enough.

I’ve thought more about what the penguins said. From their tone, I gathered they did mean make love in the literal sense, but that they meant the term broadly, as well. Make love, meaning create love. Do love. Bring love into being around you. The message is not virginal – I’d heard it plenty of times before traveling 12,000 miles to the far reaches of the planet—but then again, who expected originality? And it never hurts to hear it again —especially in another language.

That last minke, shooting from the water 200 yards to port, just as we were entering the sound. An exclamation point. When you see the last whale, of course, you do not know it will be the last, and so the intonation never drops—you do not know you are at the end of a sentence—you slide in a comma, temporarily, and keep to the deck.

I knew about the last glimpse of the continent, though, and the last icebergs. A few end stops are helpful. The last darting penguins leaping away from the bow. The last night on board ship. The last breath of air from across the convergence.

As we entered the sound, I asked Nestor lightly: “So what happens if this ship hits an iceberg?” He laughed, “I don’t know!” he said. “Something bad!”

A group of intrepid explorers returning back to the ship. (Editor’s Note: The Society Explorer hit an iceberg in November 2007 near King Geoge Island in the South Atlantic and sank. All aboard were rescued.)

I have been thinking about emperor penguins, which we did not see. Unless you are very lucky and determined or very wealthy and determined, you will never see a wild emperor penguin. I keep thinking of the males huddled on the ice in the dead of winter, their brood skin wrapped around their one precious egg; of the chicks half-suffocated in feathers, legs splayed wide in order to rest on the parents’ feet, of both chicks and parents rocked back on their heels, toes delicately held in the air, to prevent their feet freezing to the ice. What an enormous lot of time, energy, and concentration two 90-pound birds put into raising one chick each year! They must be the most life-conscious, the most non-violent, the gentlest birds in the world. What songs they must sing to themselves and their eggs as they drowse through the winter storms; and with what joy they must greet those little black and white puffballs during the austral dawn. A whole culture built around chick-raising.

Of course, then there are the female seals who are only not pregnant five days a year…

Boom! The wheels hit the runway… Peru, as a nuisance stop. Sometimes the waking is not slow.

Do I feel now, flying north, the same about Antarctica as I flew south—that it is a holy land, a stronghold of the memory of a time “before” destruction and change? Yes and no. Yes, overall. But it has been more touched by humans than I had wanted to believe. The awful, irreversible massacres of whales and seals. The ugly, trashy little “research stations” lodged on nearly every piece of ice-free land we saw. I know we went to what comparatively is urban Antarctica, the megalopolis. But still, I did not quite expect so many strewn whale bones, stone hut foundations, plaques, crosses, trash heaps. It is the most pristine, and still it is sullied… knowledge that pinches open an old, permanent sadness.

And why would the penguins tell me to make love? Perhaps because sexuality is still unsullied by the conscious mind—perhaps it is one of the tools we can use, part of the technology of intuition we have forgotten and must reteach ourselves and each other, bumblingly, with much trial and error.

I have seen the ice-littered land, the bared rock plains strewn with the abandoned pebbled nests of penguins, the horizon nuzzling the hands of clouds. I have seen the beaches littered with fur seals croaking and indignant among penguins. I have heard the deliciously longed-for exhalation of whales, fat and unhurried and good-naturedly rude, like the belches of peasants at a bar. I have heard the ice collapse in the caves and trip down the cliffs, strewing the bays with fragments—I have watched our ship nose floes heaped with dreaming seals, who woke in disgust and slipped off into the dark ice-blue caverns. I have seen ghost-white crabeaters skim wide-eyed beneath our boat, faces upturned; I have seen penguins scramble on mud-cliffs and nearly fall on their necks. I have seen night come to the glaciered bays like a long, solemn chant, with no crescendo, no pause—just a single, sustained note, bringing darkness. The twin peaks rose vertically from the fjord, the corniced summits curled dangerously toward the interior. A few times, the light came, and color entered this black-white-gray-brown land, in the brilliant blues of sky and water, the red beaks of the gentoos, the cloud-blue backs of the newly fledged chicks. Of those few hours of light, I remember only a happy confusion of colors and forms and images, of ice fusing and flaming where it met sea and sky, of glistening spotted seals and glowing penguins. Most of the time, it is not like that. If it were, the light might fade, the colors drain, the shadows blur, in time—at such times the brain turns protective and shielding and throws a towel over the eyes, who might otherwise stand hallelujahing in the downpour for days until the light washed them away.

So, I have been there, and seen it, as well as I could—and what it is supposed to mean to my life—what all this has to do with past and future—is not yet on the charts. But I have my line, my weight, my measure. The ship seems to know where it is going. Downstairs six decks, 20 souls I never saw or will see are turning the engines, adjusting the pressure, looking every now and again, from the portholes, and grinning their slow, secret grins.

Penguins have walked around me. Petrel chicks spat and hissed at my hulking rude presence. Skuas thought enough of me to nearly cleave my hair and a fur seal opened one eye when my shutter clicked. It is nice to be noticed. It is nice to leave some wake behind that is then slowly stitched into the sea.

Editor’s Note: All photos by Gale Warner unless otherwise stated.