In 1933, Sierra Club members on the peninsula south of San Francisco decided it was high time they organized their own chapter. To muster the 50 members needed to qualify, they joined forces with the young San Jose State College Hiking Club and assembled one Sunday afternoon in June in a wooded glen at Hidden Villa Ranch, owned by community leaders Frank and Josephine Duveneck.

Why Hidden Villa? “It was such a beautiful spot, and so many of our hikes started there,” remembered Dorothy Kinkade, one of the founders. ‘’Also, Frank and Josephine were always so generous and open to us. For years we had our Christmas and spring Sierra Club parties in their house, with guitars and music and folk dancing.”

Eventually, the chapter outgrew the Duvenecks’ living room. “After 150 people came one year, we decided we couldn’t handle it that way anymore,” admitted Frank. Loma Prieta is now the third-largest chapter in the country, with nearly 18,000 members, flourishing conservation and activities sections, and one perennial question: Who or what is a Loma Prieta?

Don Woods, another founder, said there was some amiable disagreement among chapter organizers as to whether the new group should be named for one of the local counties of Santa Clara and Santa Cruz: “Finally someone suggested naming it after the highest peak in the area, the Loma Prieta ‘dark hill’ in Spanish-and oh! that was a happy thought.”

Another happy thought was giving founders Dorothy Kinkade, 70, Don Woods, 80, and Frank Duveneck, 96, the kudos they deserve by holding the chapter’s 50th-birthday celebration at its birthplace, Hidden Villa Ranch in Los Altos Hills.

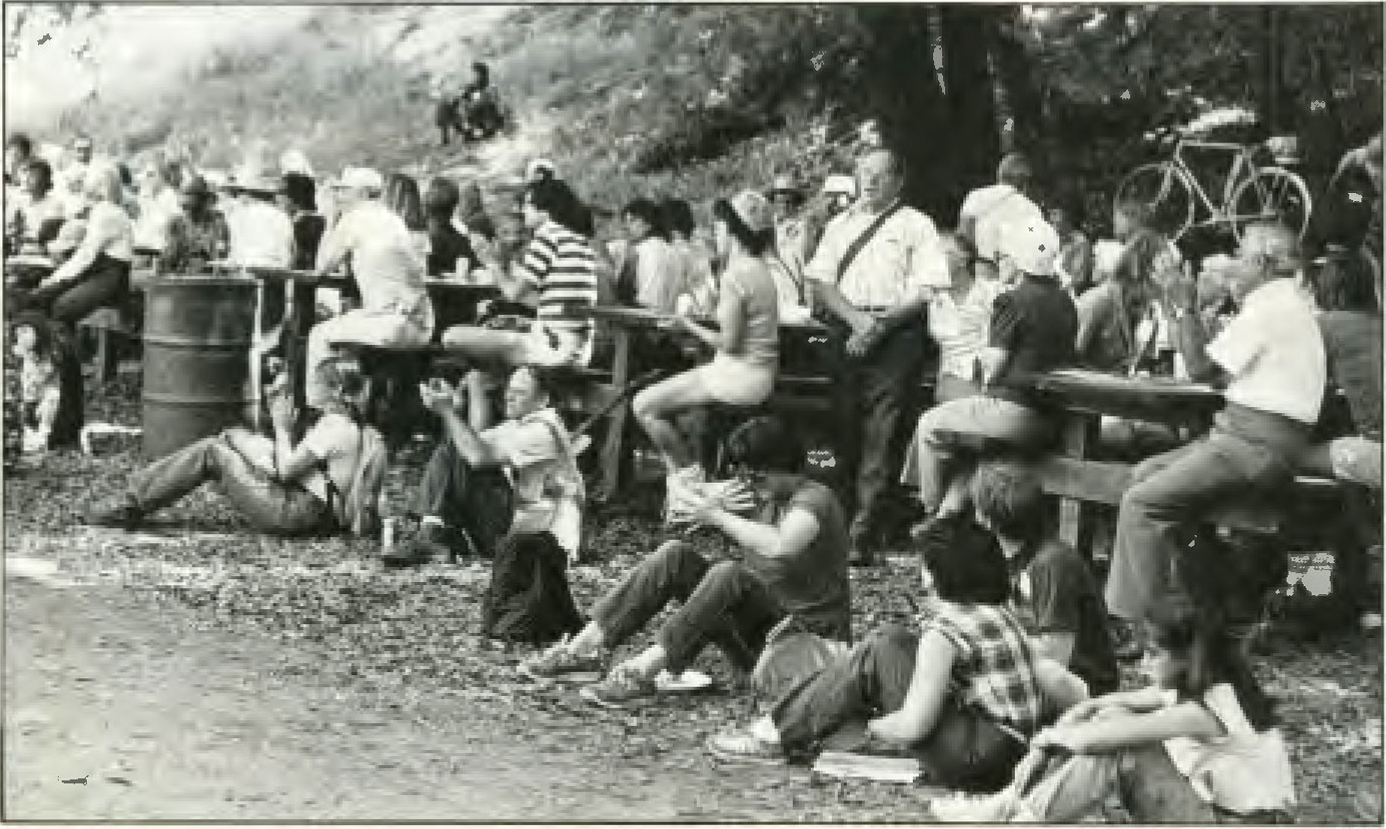

Despite some last-minute consternation created by the realization that 18,000 people had been invited, a pleasant crowd of 300 gathered for the bash under arched bay trees at Hidden Villa’s picnic area on June 12, 1983. And despite some speculation that the occasional planes passing overhead might be conducting reconnaissance flights for James Watt, who might have considered launching a preemptive strike against such a large concentration of environmental extremists, the party went off without a hitch.

Members came to climb 2,787-foot Black Mountain, admire birds and wildflowers on shorter walks, sing along with a guitar-playing troubadour, read pamphlets, sign petitions, trade environmental updates, volunteer for task forces: in short, to do what Sierra Clubbers do best. Food, drink, and general merriment were abundant. Except for the “Wanted: James Watt” poster on the barbecue stand and the well-marked box for recycling aluminum cans, even Ronald Reagan would have been hard-pressed to find fault with the picnic’s old-fashioned, All-American flavor.

Sierra Club cups hung proudly from more than one old-timer’s belt, and reminiscences flew over the scrapbooks many had brought along. On the other end of the generation scale, youngsters gawked at the pigs, cows, and lambs of Hidden Villa’s educational farm and marveled at the softness of a baby rabbit’s fur.

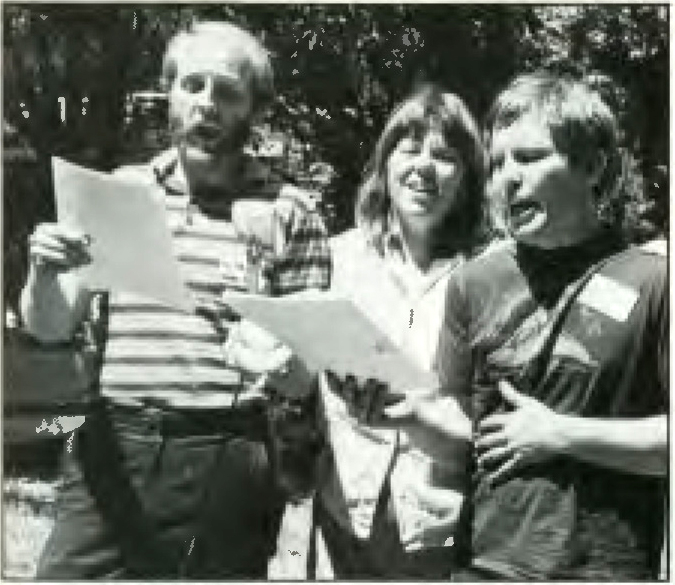

One of the high points of the afternoon was the unabashed performance of a musical satire written by Bob Reid that cleverly filched tunes from My Fair Lady. Jeff Norment, Marlene Mandt, and Chapter Chair Al Henning crooned such titles as “I Could’ve Logged All Night,” “I’m So Bewildered by the Parks,” and “Get Me to the Bank on Time.” Henning’s mellifluous rendition of the following ditty (to the tune of “On the Street Where You Live”) was especially memorable:

I have felt so much like a helpless chump

Since I learned my house was built upon a toxic dump.

I have lost my yens

For carcinogens,

‘Cause they’re there in the house where I live.

Are there PCBs in my underwear?

Is asbestos in my salad or my TV chair?

Where I go to sleep

Do dioxins seep

Through the floor of the house where I live?

Famed historian, author, and wilderness advocate Wallace Stegner, who is also a longtime friend and neighbor of the Duvenecks, was on hand to add some thoughtfulness to the shindig. “Our mission now is to love and husband the earth,” he said. “That’s a more complicated task than the outdoorsmen and nature lovers who gathered here 50 years ago had yet thought of… but they would have understood it, and they would have been on our side.”

Stegner presented Kinkade, Woods, and Duveneck with engraved, gold-plated Sierra Club cups and with certificates recognizing their roles as charter members. Elise Yulich, daughter of another chapter founder and a member since 1930, also received an award, and other old-timers present-Jerry and Ruthie Parrish, Alice and Herman Horn, Katy Reed Madsen, Bob Cassel, Stacy and Margaret French, Arnold Robinson, and Harvey Dowling—were saluted with a “50th birthday” cake.

“I got into the Sierra Club by mistake because I owned a lot of property around here,” joked Frank Duveneck. In fact, Frank and his family have been not only preaching but practicing conservation and land stewardship for almost 60 years.

Frank and his wife, Josephine, both of prominent Boston families, came to California during World War I and bought Hidden Villa’s original 1,000 acres in 1923 for $25 an acre. Eventually, they added enough land to control the Adobe Creek watershed and protect it from the urban sprawl that even then threatened their neighborhood.

The Duvenecks’ hospitality effectively turned their private land into a public park. Open to all for hiking, riding, and picnicking, the 1,800-acre ranch serves as a vitally necessary wildlife sanctuary and rural oasis in the urbanized so-called Silicon Valley. “My wife and I felt that the land really belonged to the deer, the bobcat, and the other wild things that live here,” said Frank. “We simply held it and took care of it.”

Wallace Stegner once termed Hidden Villa “a remarkable monument to one couple’s imagination, energy, humanity, and good-will.” The ranch sheltered European refugees from World War II and Japanese-Americans returning from domestic internment camps. Indians, Chicanos, blacks, farmworkers (Cesar Chavez began organizing his agricultural-workers’ union here), and civil-rights activists-not to mention environmentalists-have all used Hidden Villa as a friendly meeting ground. The Duvenecks initiated many programs on their property, including the Pacific Coast’s first youth hostel, a pioneering multiracial summer camp for children (that raised many eyebrows in 1945), and backpacking trips to the Coast Range and the Sierra for teenagers. But the ranch is probably most famous for its Hidden Villa Environmental Project, one of the most innovative and successful environmental-educational programs in the country. In 1970 HVEP staff members, with the help of trained volunteer guides, began giving children from local elementary schools an all-day, small-group experience -meeting the farm animals, hiking the wilderness trails, and learning ecological concepts of cycles, energy, interdependence, land use, and human responsibility. Younger children also travel to the farm in larger groups to view the living origins of their meat, milk, and eggs. Some 7,000 children now visit Hidden Villa every year.

Appropriately, HVEP staff naturalist Mary Hallesy, known to thousands of peninsula children as “the lady in the red hat with all the buttons,” received her National Service Award at the June 12 ceremony for her long list of contributions to the Sierra Club, including revival of the LeConte Lodge program in Yosemite National Park. Ollie Mayer, another National Service Award winner for her work on a score of open-space and conservation issues, was also cheered. As Chair Henning remarked, it is a tribute to chapter’s energy and leadership that two of three recipients of the Sierra Club’s National Service Award this year were Loma Prietans.

But if the enthusiasm displayed by all ages of Sierra Club members that day is any indication, it won’t be the last time the chapter is singled out. Frank Duveneck believes the Sierra Club should concentrate on protecting forest lands and preventing exploitation by commercial interests, but he also supports more recent additions to the Club’s list of concerns, such as nuclear weapons. “I’m very much along with the rest of the Sierra Club. I think we can put in quite a bit of punch,” he declared. “I don’t think the battle is won yet, but I think we’re on the way.”

Gale Warner is a freelance writer from Ashville, Ohio, whose work has appeared in New Age, the Boston Globe, the Christian Science Monitor, and Sanctuary.

Reproduced with permission from Sierra Magazine, Sept./Oct. 1983