There are times when the life of a person and the history of a place become so enmeshed that the story of one is necessarily the story of the other. Ninety-six-year-old Francis Boott Duveneck ’05 and his beloved Hidden Villa Ranch in Los Altos Hills, California, have lived in a symbiotic partnership for so long that their personalities have merged, creating a cooperative whole that transcends the limits of a single individual or location.

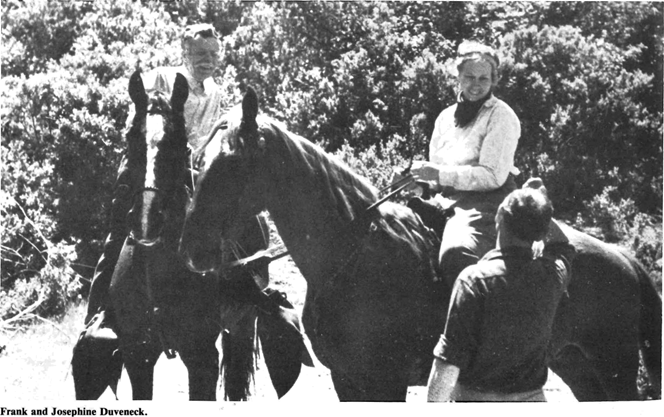

This beneficent partnership began almost as soon as Frank and his wife Josephine discovered Hidden Villa in 1924. “We opened the gate, passed by a closely planted olive grove and continued up the lane past open pastures in which a few cows were grazing,” wrote Josephine in her autobiography. “We discovered there was an old ranch house, a splendid wooden barn and a number of out-buildings. Most exciting of all, a running stream came meandering down out of the hills and through the fields to the road. What a beautiful place! What a playground for children! What opportunities for gardening, for raising animals, for country living!

“When I first walked up the road in Hidden Valley, I was overwhelmed by a sense of past lives lived in serenity and harmonious fulfillment here. I have continued to have an abiding sense of the sacredness of this environment, especially after all of our years here, because of a sense of the accumulation of enjoyment and appreciation left behind by children and adults who constantly visit us. We purchased the land because we fell in love with it, and it has been our policy ever since to preserve and cherish its pristine beauty for other lovers of nature now and in future generations.”

But the Duvenecks have done far more than merely preserve what they found. They worked to make Hidden Villa a place where the injustices they saw around them could be healed, where the new ideas they saw as necessary in our society could be nurtured. Though most of the land remains unspoiled wilderness, they have imbued it with their personality so forcefully that casual hostel visitors and lifelong ranch residents alike can feel their presence in the land.

Rent Dubos coined the phrase “humanized landscapes” for places such as Hidden Villa, “where human effort has brought to light values that transcend those created by natural forces working alone.” Because it has many of the complexities and intangible qualities of a human being, describing Hidden Villa is not an easy task.

It encompasses 2,000 acres of grassland, chaparral, and bay-oak forests in the foothills of the Santa Cruz Mountains, including the entire watershed of Adobe Creek. It is a working farm with a garden, orchard, and domesticated animals such as cows, horses, pigs, goats, sheep, chickens, and rabbits. It is a site for many educational programs: an inter-racial summer camp, an environmental education project for elementary school children, farm tours for preschoolers, backpacking trips for teen-agers, and a horsemanship center. Its many other community activities include crafts fairs, festivals, folk dances, riding shows, and gatherings of a score of social, conservation, and humanitarian groups at its youth hostel.

But like any resume, this picture is incomplete. It fails to capture the spirit of Hidden Villa, the sense of harmony and restfulness here that goes beyond its physical beauty. It fails to tell the individual stories: a World War II Jewish refugee coming here to be reoriented to a new life, a foster home child transformed by her summer camp experience, a disillusioned college student inspired by his volunteer experiences to become a teacher, a ghetto child awestruck by a chance to pet a calf.

To understand what Hidden Villa is today requires digging into its past. The high society of Victorian era Boston seems very distant when one walks a steep trail at Hidden Villa, spotting lizards and smelling sage and toyon after a winter rain. Yet the story of Frank and Josephine and thus Hidden Villa, begins there.

Frank was born in Florence, Italy, in 1886 into an artistic and sophisticated family. His mother, Elizabeth (Lizzie) Lyman Boott, was born in America but raised and educated in Italy by her father, Francis Boott. Many wellknown literary figures frequented the Boott’s Villa Castellani, including Henry James, who corresponded with Lizzie for many years and incorporated her into The Portrait of a Lady.

A talented watercolor artist, Lizzie studied with the American painter Frank Duveneck, and a romance developed between pupil and teacher that lasted ten years before their eventual marriage against the wishes of Lizzie’s father. “Frankie” was soon born, but Lizzie died suddenly in Paris in 1888 and the stricken father and grandfather accepted the invitation of the boy’s maternal great-aunt, Mrs. Arthur Lyman, to raise him in her home in Boston.

Frank thus grew up in the solicitous and privileged atmosphere of the Lyman’s Beacon Hill mansion and Waltham summer estate. As a boy he surprised his family by showing an aptitude for mechanical tinkering, asking for a shop rather than a studio and tools rather than paints.

Attending Middlesex School gave him his first chance to live outside of his protected home atmosphere. “I was a very spoiled child at home,” says Frank, “and it was a darn good thing for me to get out. I did a reasonably unsatisfactory job at Middlesex except in mathematics and the very small amount of shop they had then. So the headmaster, Mr. Winsor, told me to go into engineering, which turned out to be a very important piece of advice.

Otherwise, I might have gotten stuck doing something I wouldn’t have enjoyed.”

At that time, gentlemen from prominent families were expected to go into business, law, or medicine; engineering was considered more plebian. But Frank attended Harvard and received a master’s degree in mechanical engineering, a subject he later taught at both Middlesex and Harvard. While a graduate student, he met Josephine at a debutante ball in 1910.

Josephine later confessed that at first Frank did not impress her much; he seemed quiet and reserved, only asking her to dance a few times. Josephine Whitney was also raised in a wealthy Boston family, but always felt herself to be something of a misfit in society life, preferring music, writing poetry, and walking in the woods to debutante parties and balls.

On Frank’s side, he claims that he decided to marry Josephine the first moment he laid eyes on her. But after graduation he did not pursue her for several years. “I wasn’t a big fool — I didn’t think I was a person in any sort of a position to ask anyone to marry me!” laughs Frank. Anxious to get away from Boston, Frank journeyed to Panama to watch the building of the Panama Canal, then worked for Westinghouse Company in Pittsburgh. Only after his return to Boston from a European trip with his ailing father did he send Josephine a request for the title of a piano piece she had once played for him and a suggestion that she might invite him to visit.

Meanwhile Josephine had taken some classes at Oxford and was making plans to strike out on her own career in New York. But the unexpected reappearance of Frank, and their discovery of a mutual love of music, animals, and the outdoors, led to their marriage in King’s Chapel in 1913.

The newlyweds travelled in Europe and the Orient for a year before returning to Boston to settle down. On their way to Japan they visited relatives in California, and, immediately entranced by the warm weather and miles of orange groves, talked of retiring there in their old age.

But a long New England winter accelerated that plan. Frank had taken a job in a Lowell mill, and the Duvenecks spent a miserable winter with their two small children in an inadequate house where “when the wind blew, the curtains at the windows would billow out into the room, and the carpets would ripple across the floor like waves.” California not only offered warmth, but a chance to escape from pressures of conformity coming from family and acquaintances in Massachusetts. They moved to California in 1917, just after the United States entered World War I.

Frame Duveneck ’05 is the School’s oldest living alumnus.

“When I came out here there was absolutely nothing to do in my line of work,” says Frank. “I didn’t think that someone who had had the easy life I’d led should just stand by and let other people do the work. It was up to me to do something, so I enlisted in San Francisco. I suppose that sounds crazy — you do all sorts of crazy things when you’re that young.”

Frank joined the 322nd Field Signal Battalion as a way to contribute his technical skills without being called to bear arms. After serving in the Combat Zone, he was assigned to the Army of Occupation in Germany for nine months of waiting for the peace treaty to be signed.

While there he befriended young German children who used to come and learn baseball from the bored American soldiers.

“I think that we think of Germany as having been terribly wicked at the time of Hitler, but there were a lot who didn’t go for Hitler, and they couldn’t do anything about it,” comments Frank. “Perhaps it was a very fortunate thing for me to be in the Army of Occupation. Josephine was rather surprised when I got home that I didn’t feel any bitterness against the Germans.”

After the family was reunited in Palo Alto, the Duvenecks took many camping trips to explore the wild country around them, piling their four children in a Model T Ford and heading for Carmel, Big Sur, and the Santa Cruz Mountains. Returning from one of these trips, they glimpsed “a seductive little green valley” nestled in untouched woodland below them, and wondered how they could reach it without fighting through thick chaparral brush.

Hidden Villa had been inhabited for centuries before the Duvenecks’ arrival, but its history is shadowy and full of legends with details softened with time. It is likely that Ohlone Indians once lived by Adobe Creek, catching salmon, making bread from acorn and buckeye meal, and fearing grizzly. Later, Spanish padres replaced them and are rumored to have planted the large olive grove at Hidden Villa’s entrance. Some of the ranch buildings, including a recently restored redwood barn, were built in the 1860s. One old ranch house is said to have been transported in pieces around Cape Horn, and at one time served as a stagecoach stop for the three-day trip from San Jose to San Franclsco.

On a subsequent excursion the Duvenecks found the gate to Hidden Villa, and, once inside, realized this was the valley they had admired from above. Within a week they bought the original 1,000 acres, and gradually added enough land to preserve the entire watershed. At first the ranch was only a weekend retreat, but in 1929 they built a new house and made it their permanent home.

The story of Hidden Villa might have ended there were it not for the Duvenecks’ unique philosophy of land ownership. “How can we own what we did not create?” asks Frank. “We are only the custodians of the land, and have a responsibility to let others enjoy it. We simply held it, and took care of it.” Thus the gate to Hidden Villa remained open. The Duvenecks saw the ranch as an opportunity to put their conservation and humanitarian ideals to practical and direct use.

One of their first projects was establishing a youth hostel in a side canyon. Hosteling had developed in the United States after the model of the German Jugend Herberge, a program to provide safe and inexpensive shelter for travelling young people. The Duvenecks opened their small hostel in 1937 as the first affiliate of the American Youth Hostel Association on the Pacific Coast. Today, it welcomes bikers, hikers, and other visitors from all over the world and serves as a weekend retreat for many organizations, offering rustic cabins in a canyon filled with bay trees and an atmosphere of shared labor and hospitality.

“Children are the most important crop we grow here,” says Frank, and in 1945 the Duvenecks set up a summer residential camp in order to make Hidden Villa available to more children. Combining a concern with racial prejudice with a desire to let children experience nature in a deep and meaningful way, they decided their camp should bring together children and counselors from a variety of social, ethnic, and economic backgrounds. As Josephine said, “It seemed to me if one could get hold of children before prejudice intervened there might be a good chance to prevent its development.”

Such a thing was unheard of at that time, and there were many dire predictions of failure and strife. But thanks to its philosophy of accepting and learning from individual differences, based on a mutual respect for each person’s way of life, the camp has flourished. Although demand is so high that all places could easily be filled by paying campers from middle-class and affluent families, the camp remains committed to its original goals, and half the children come from ghettos, foster homes, and minority neighborhoods on donated funds. Every summer Hidden Villa becomes a small but bubbling melting pot.

A concern for international brotherhood and peace has long been an integral part of the Duvenecks’ ideals and actions. An avid landscape gardener, Frank has planted trees and shrubs from all over the world around his home, and likes to point out that they seem to be able to mingle roots and share the sunshine very well. One diminutive Japanese cherry tree “which had never done anything interesting until then” bloomed unexpectedly a few days after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

The war was a busy time for the Duvenecks, with many shattered lives to heal. Many conscientious objectors came to Hidden Villa to write their agonized statements about why they felt they could not serve. Through their involvement with the Society of Friends and the American Friends Service Committee, the Duvenecks took in many refugees of the war, especially Jewish intellectuals out of Germany and Austria.

Some of the refugees came from their own community; in 1942 all persons of Japanese descent were ordered to evacuate their homes and report to concentration camps. Appalled by this breach of democracy, the Duvenecks led the fight against this action and later helped the returning Issei (those born in Japan) and Nisei (their American-born children) to find jobs and relocate after the war.

Nearly every minority group in California was at some time or other aided by the Duvenecks’ standing offer of a friendly place to meet. Many blacks had moved into the Bay Area to labor in Oakland shipyards and other industries during the war, and the Duvenecks attempted to facilitate their acceptance into local communities by helping form and perpetuate the California Federation of Civic Unity. They were also active supporters of the Bay Area Indian Council, which worked to insure fair treatment of remaining Native Americans in California.

One of the most famous organizers to get his start at Hidden Villa was Cesar Chavez, who became a personal friend of the Duvenecks and held some of the first organizational meetings of the Agricultural Worker’s Union at the ranch.

“We’ve always been interested in the outdoors,” says Frank in an understatement; caring for the environment and preserving open land amidst encroaching subdivisions and urban sprawl has been a continuing mission of Hidden Villa. The Lorna Prieta chapter of the Sierra Club was founded on the property in 1933, and the Duvenecks fought in many conservation battles close to and far away from home. Through these experiences they learned that a sense of caring for the earth comes from a personal relationship to living things that is best implanted and nurtured in early childhood.

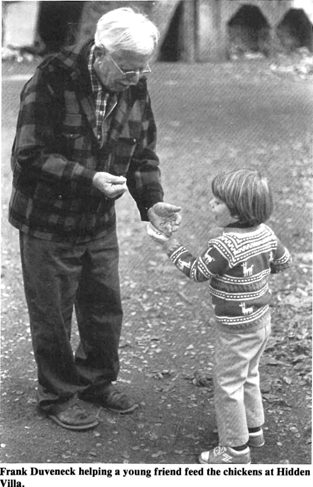

Already thousands of preschool and kindergarten children had been visiting Hidden Villa on short tours that introduced them to cows, chickens, and pigs, allowing them to realize, often for the first time, where their meat, milk, and eggs come from. For the older children the Duvenecks knew that a more in-depth experience was needed.

In 1970, the year of the first Earth Day and the beginning of a growing concern for the environment in this country, the Hidden Villa Environmental Project was launched with a staff of three, a sense of mission, and a willingness to try new things. Today it is well known as one of the largest arid most successful environmental education programs in the country. Some 3,000 children a year, from the second through sixth grades and from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds, travel to Hidden Villa to learn about a working farm, natural history, food webs, interdependence, and human responsibility through creative strategies that emphasize a hands-on approach.

In small groups led by trained college and community volunteers, the children pet banana slugs, wade in creeks, feed chickens, cast tracks, pick through coyote scat for bones, coax baby lambs over to be petted, make tea from wild mints along the trail, hug trees, spin wool, hold snakes, tell stories, turn over a compost pile, pull and taste carrots, and are prodded to more fully see, smell, hear, taste, feel, and enjoy their surroundings. HVEP asks the children as many questions as it answers, and attempts to go beyond the mastering of facts to exploring the feelings the children have about the living things they encounter.

In the 1970s the summer programs also expanded to accommodate the number of camp graduates who wished to continue to spend their summers at Hidden Villa. “Bay to the Sea” hikes, trail camp, backpacking trips to the Sierra mountains, and bicycling trips along the coast are now offered to teenagers, and as with all of Hidden Villa’s programs, a substantial number of participants come from underprivileged groups on scholarships.

Perhaps the most simple yet the most pervasive of the Duvenecks’ policies has been the openness of Hidden Villa to picnicking, jogging, hiking, and reflection, providing an escape from the density and pressures of the nearby megalopolis. The sight of couples jogging, babies in strollers, and the sound of children laughing on the hillsides does not detract but adds to Hidden Villa’s ambience.

The Duvenecks were not content to merely sponsor programs, but were leaders in getting them off the ground, shaping them, and making them work. If Josephine was often the charismatic organizer, Frank was the behind-the-scenes workhorse, invaluable as plumber, electrician, mechanic, carpenter, blacksmith, and all-around fixer of things.

Shortly after celebrating her 65th wedding anniversary with Frank, Josephine died in 1978.

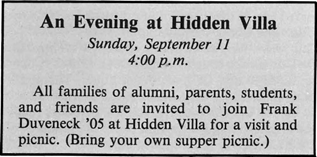

But Frank, at 96, shows few signs of slowing down. In 1959 the Duvenecks created a nonprofit corporation, Hidden Villa, Inc., to manage the programs at Hidden Villa.

Culminating a lifetime of giving, Frank and his family plan to donate all but 40 acres of Hidden Villa’s property to the corporation to assure the continuation of its educational programs. Hidden Villa, Inc., is now looking for ways to assume the additional financial responsibility of managing the land and the farm’s equipment, facilities, and animals.

Frank is often seen around Hidden Villa, walking to fetch the mail or reading his voluminous correspondence at a sunny window. Still championing his various social causes, he worries about the nuclear arms buildup, the destruction of forest wildernesses, and governmental cutbacks in education. Children remain his favorite visitors, and he awes them with his age and gentle warmth, often telling them his favorite story of “the time the cow didn’t come home.”

But Frank seems especially at home in the armchair in front of the large hearth where he has welcomed so many. As a group listens, he recalls the first time he lighted a fire in the new house. “It was just an empty shell then,” he says. “It had no personality. What has made it special is the accumulation of all the personalities of the people who have visited us. All of you being here is what has made this into a home.”

A native of Ohio and recent graduate of Stanford University, Gale Warner is a freelance writer who has published in The Boston Globe and The Christian Science Monitor. She now lives and works at Hidden Villa Ranch as an intern with the environmental project, “a job that includes mucking the sheep pen, guiding third graders, cleaning the hostel, consulting on publicity, planting tomatoes in the garden, and absorbing all the rfch experiences Hidden Villa has to offer.”